bold blue, red hill

Exhibition by Caitlin Clarke

bold blue, red hill | Caitlin Clarke | Wave, Ōtepoti

05.07.22 | written by Simon Palenski

About a month before the opening of bold blue, red hill at Wave, artist, writer, and educator Vicki Lenihan held Ōtepoti Stor(i)es at Blue Oyster. Lenihan had organised an exchange: visitors were asked to bring donations of food for Te Whare Pounamu Dunedin Women’s Refuge, in return Lenihan offered a degustation meal in rourou and a jar of either plum chutney, jam, or sauce made herself with fruit from an old and bountiful tree in her garden. After people had dropped off their donations and chosen a jar of preserve, Lenihan shared the origins of the name Ōtepoti and how the area across the street from Blue Oyster, facing Queen’s Garden, used to be the sheltered part of the harbour where markets and trade took place, as early colonial settlers up on the hill met and traded with hapū who visited from Ōtākou and further afield. Without this crucial trade link, the early colonial settlement would have likely run out of food.

Wave is a new project space in Ōtepoti founded by Kari Schmidt who co-founded Laurel Project Space (which is still running, with a name change, as Favour). bold blue, red hill is Wave’s second exhibition, the first having been James Varga’s Goldfish Bowl. The gallery space takes up two adjoining rooms on the ground floor of a three storey warehouse at 1 Vogel Street on the other side of Queen’s Garden. The front corner room with windows onto the street is the exhibition space, while the back room with couches and rugs is for hosting events/serving drinks and snacks. The history of Wave’s immediate surroundings, specifically the demolition and flattening of Bell Hill and the subsequent redistribution of the hill’s rock and soil across the harbour as part of land reclamation, is the conceptual focus for Ōtautahi-based artist Caitlin Clarke in her pottery and sculpture in bold blue, red hill.

Clarke’s aggregate habit of gathering and recycling her materials runs through the exhibition. Within this body of work there’s a series of tile-like hanging works she calls windows, ‘plates’ holding clusters of pit-fired stones and sea glass, rocky sculptures placed on the window sills, and a wall painting with clay and dirt applied in broad strokes. Centrally placed on a plaster plinth is a ceramic vase; patches of granite sands mottle its surface and pebbles fill its lips and grooves. The smoother surfaces are smeared with a blue celadon glaze — a glaze made by the late potter Rosemary Perry, which Clarke found at her shared pottery studio and was told is probably 30 to 40 years old and now impossible to recreate.1 Filtering throughout is a sound work of trickly rainy recordings made by Clarke and arranged by composer Alex van den Broek.

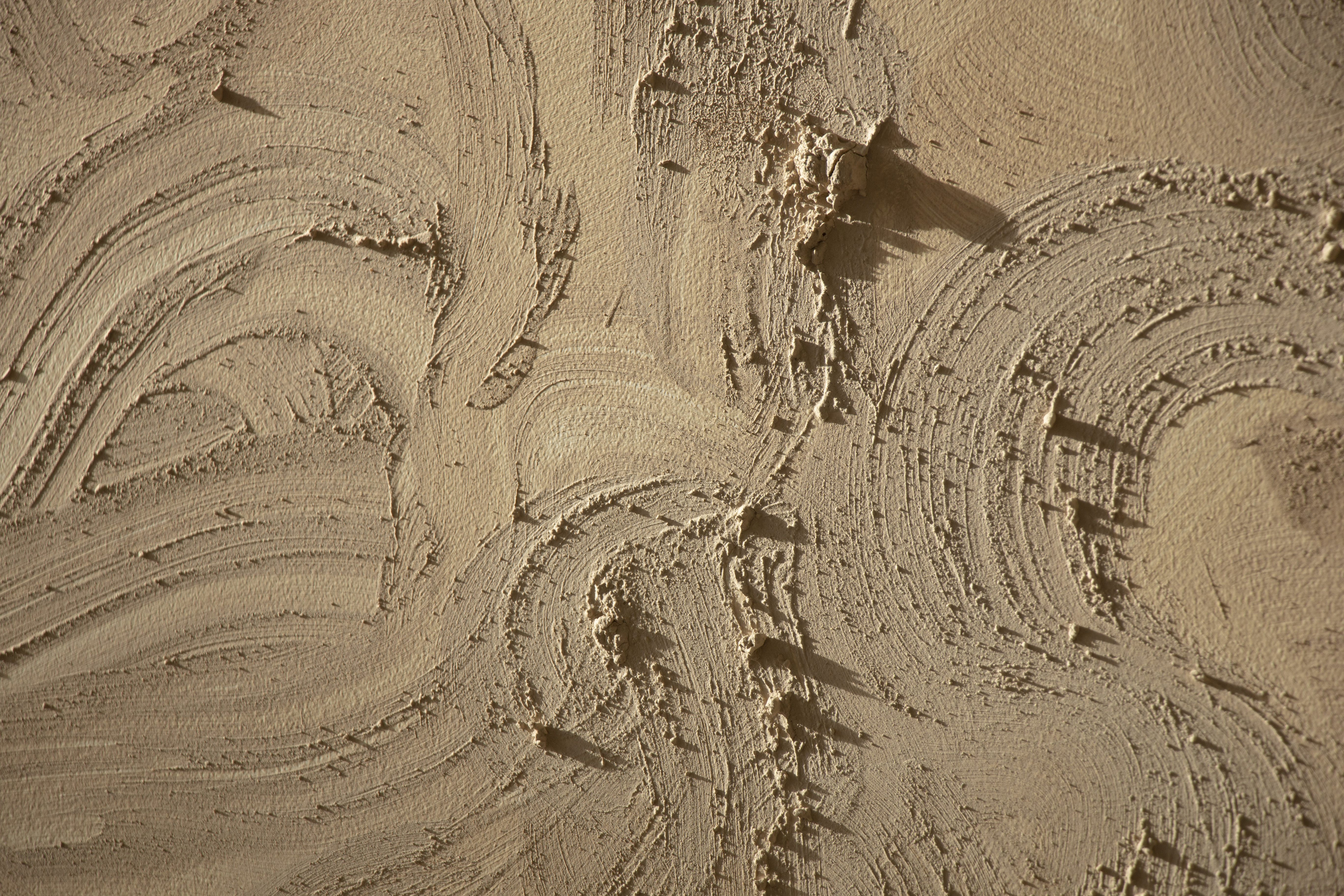

Clarke widely uses clay from multiple sources, some commercial, some recycled, and some personally dug up from sites around Te Waipounamu noted in the materials list. She told me that part of her process includes returning to sites where she has dug out clay, and putting pots she made with the clay back into the earth. One of these sites is Naseby where the land surrounding the town has been permanently altered and ruined by gold-sluicing. Clarke can trace her family back through to miners and sluicing operators, and it seems that a critical part of her ceramic and sculptural practice is an attempt to find ways to negotiate this history of wilful manipulation of the earth for colonial and commercial ends. In Clarke’s rocky sculptures there is an echo in miniature of this kind of endeavour; the folly of trying to recreate a stone exists in the same hubris of rearranging entire landforms. The wall painting too, with its round peak almost brushing the ceiling, seems to act like an afterimage of the now absent geography of Bell Hill.

Clarke’s aggregate habit of gathering and recycling her materials runs through the exhibition. Within this body of work there’s a series of tile-like hanging works she calls windows, ‘plates’ holding clusters of pit-fired stones and sea glass, rocky sculptures placed on the window sills, and a wall painting with clay and dirt applied in broad strokes. Centrally placed on a plaster plinth is a ceramic vase; patches of granite sands mottle its surface and pebbles fill its lips and grooves. The smoother surfaces are smeared with a blue celadon glaze — a glaze made by the late potter Rosemary Perry, which Clarke found at her shared pottery studio and was told is probably 30 to 40 years old and now impossible to recreate.1 Filtering throughout is a sound work of trickly rainy recordings made by Clarke and arranged by composer Alex van den Broek.

Clarke widely uses clay from multiple sources, some commercial, some recycled, and some personally dug up from sites around Te Waipounamu noted in the materials list. She told me that part of her process includes returning to sites where she has dug out clay, and putting pots she made with the clay back into the earth. One of these sites is Naseby where the land surrounding the town has been permanently altered and ruined by gold-sluicing. Clarke can trace her family back through to miners and sluicing operators, and it seems that a critical part of her ceramic and sculptural practice is an attempt to find ways to negotiate this history of wilful manipulation of the earth for colonial and commercial ends. In Clarke’s rocky sculptures there is an echo in miniature of this kind of endeavour; the folly of trying to recreate a stone exists in the same hubris of rearranging entire landforms. The wall painting too, with its round peak almost brushing the ceiling, seems to act like an afterimage of the now absent geography of Bell Hill.

Caitlin Clarke, Mossy Border, 2022. Naseby Clay, recycled clay and commercial clay with foraged sea glass, seashells, Volcanic stones from around Banks Peninsula and Basalt stones from Te Oka Bay, with Various ash glazes. Electric fired. Photo by Caitlin Clarke.

Accompanying the exhibition is a page-long story titled ‘My arm smelt of moss’ where a shifting, nameless subject rambles around the boggy inlets and sunken landmarks of a future Ōtepoti. Loulou Callister-Baker has written a response too where she imagines Queen’s Garden rapidly reverting back to shoreline marsh, and herself sinking deep into the muddy ground. Clarke’s amorphous ceramics suit this kind of science-fiction lens with their bubbly and melty surfaces and forms. But then the images of rising water and sinking land are uncomfortably real in this ‘reclaimed’ part of the city and, also, over the hill in South Ōtepoti where some of this imagery stems from, as Clarke’s Grandmother lives in St Kilda and her house has been flooding each time it rains.

The deliberate mixing of minerals and materials from different sources and the mixing of speculative fictions with recorded colonial history reflects Clarke’s interest in liminal environments like shorelines and estuaries, places that are in-between. Some natural looking elements of the exhibition partly share this in-betweenness. On first glance, the plinths for the ceramics look like replicas of rocks, their surfaces covered in soil coming alive with sprouting plant life. But they are plaster casts of the negative space between groups of rocks, poured, set then tipped upside down, with the soles of their soiled feet forming the plinth. Clarke’s ‘window’ tiles form a kind of in-between space too. The idea of calling the hanging tiles windows comes from the origin of the word, the Old Norse vindauga meaning wind eye, and they offer a literal compositional window or eye into the clays, sands, stones, ashes, and sea glass that make up Clarke’s sculptures and ceramics. Lines lifted from Seamus Heaney poems provide titles for some of these; ‘Better sunk under’ and ‘I composed habits over acres.’ I enjoyed the link between these titles and another book, P. V. Glob’s classic The Bog People, which I am sure Callister-Baker must have read, and which Heaney was a fan of too.

Clarke lets the raw elements in her work show their inherent character; gathered together, they warp and split in their own language. The speculative fictioning of bold blue, red hill might unsettle some of the rhythms that exist in the streets around Wave, tending to what has been smoothed flat in the fading present.

The deliberate mixing of minerals and materials from different sources and the mixing of speculative fictions with recorded colonial history reflects Clarke’s interest in liminal environments like shorelines and estuaries, places that are in-between. Some natural looking elements of the exhibition partly share this in-betweenness. On first glance, the plinths for the ceramics look like replicas of rocks, their surfaces covered in soil coming alive with sprouting plant life. But they are plaster casts of the negative space between groups of rocks, poured, set then tipped upside down, with the soles of their soiled feet forming the plinth. Clarke’s ‘window’ tiles form a kind of in-between space too. The idea of calling the hanging tiles windows comes from the origin of the word, the Old Norse vindauga meaning wind eye, and they offer a literal compositional window or eye into the clays, sands, stones, ashes, and sea glass that make up Clarke’s sculptures and ceramics. Lines lifted from Seamus Heaney poems provide titles for some of these; ‘Better sunk under’ and ‘I composed habits over acres.’ I enjoyed the link between these titles and another book, P. V. Glob’s classic The Bog People, which I am sure Callister-Baker must have read, and which Heaney was a fan of too.

Clarke lets the raw elements in her work show their inherent character; gathered together, they warp and split in their own language. The speculative fictioning of bold blue, red hill might unsettle some of the rhythms that exist in the streets around Wave, tending to what has been smoothed flat in the fading present.

Caitlin Clarke, bold blue, red hill, 2022. Wall detail. Photo by Liam Hoffman.

Caitlin Clarke, bold blue, red hill, 2022. Wall detail. Photo by Liam Hoffman. Caitlin Clarke, bold blue, red hill, 2022. Installation view. Photo by Liam Hoffman.

Caitlin Clarke, bold blue, red hill, 2022. Installation view. Photo by Caitlin Clarke. (Both above images)

Caitlin Clarke, bold blue, red hill, 2022. Installation view. Photo by Caitlin Clarke. (Both above images)Caitlin Clarke, bold blue, red hill, 2022. 3 – 25 June 2022 at Wave, Ōtepoti.

Photos: Courtesy of the artist, the photographers, and Wave Project Space.

Article image: Caitlin Clarke, Tidal plate, 2022. Detail. Photo by Caitlin Clarke. Clay dug from Wainui, recycled clay, Dunedin Yam clay, Southland clay and commercial clay. Hakatere Stones and foraged Stones from Charteris Bay with stones from artists collection sourced from around Te Waipounamu.

1. Caitlin Clarke in conversation with the author.

Photos: Courtesy of the artist, the photographers, and Wave Project Space.

Article image: Caitlin Clarke, Tidal plate, 2022. Detail. Photo by Caitlin Clarke. Clay dug from Wainui, recycled clay, Dunedin Yam clay, Southland clay and commercial clay. Hakatere Stones and foraged Stones from Charteris Bay with stones from artists collection sourced from around Te Waipounamu.

1. Caitlin Clarke in conversation with the author.

ISSN 2744-7952

Thank you for reading ︎

Vernacular logo designed by Yujin Shin

vernacular.criticism ︎