Wild Once More

Exhibition curated by Christopher Ulutupu

Wild Once More | Aliyah Winter, Connor Fitzgerald, Daniel John Corbett Sanders, Laura Duffy, Neihana Gordon-Stables, Sorawit Songsataya | Te Tuhi at Silo 6, Tāmaki Makaurau

12.04.22 | written by Robbie Handcock

Working in the arts in Aotearoa means you inevitably work with friends. The mixing of the personal and the collegial is hard to avoid in an industry and country of this size. Wild Once More, an offsite Te Tuhi exhibition held at Wynyard Quarter’s Silo 6, developed from a podcast series I hosted for CIRCUIT. Titled Popular Glory: Contemporary Queerness and the Moving Image, it involved a series of interviews with “a range of Aotearoa artists working in moving image who employ queerness as identity, content and strategy” and also comprised mainly of friends. Four artists from this series — Aliyah Winter, Daniel John Corbett Sanders, Laura Duffy, and Neihana Gordon-Stables — along with Connor Fitzgerald and Sorawit Songsataya came to constitute the exhibition Wild Once More. In the spirit of full disclosure, the exhibition was initiated by me but due to workload and personal circumstances, it was another podcast interviewee, the artist Christopher Ulutupu, who ultimately curated this exhibition.

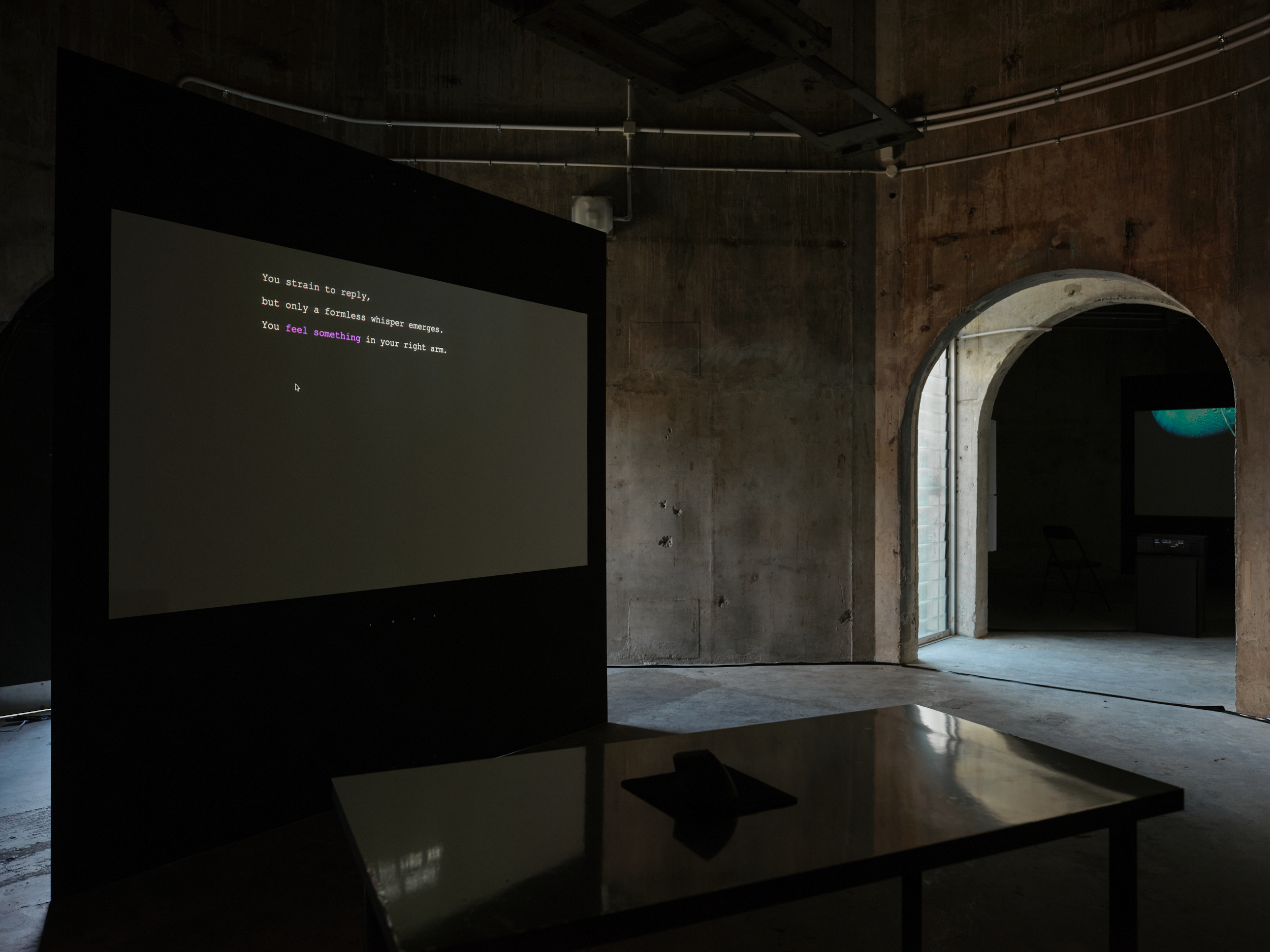

Curatorially, the works are divided into two groupings. The first grouping — titled Glancing into the wilderness— includes works by Aliyah, Sorawit and Laura that “evoke disruption and rupture the very fabric of reality.”1 The visitor is greeted by Aliyah’s restoration fibre song (2022), a poetic text-based ‘choose your own adventure’ type game controlled by an ergonomic mouse on a metallic silver-surfaced table. On a black screen, the sentence, “You wake up, swathed in white cloth” appears in white and purple text, with the purple indicating clickable options. The visitor clicks through until they reach a screen with the word “YOU” in purple, repeated multiple times like lines on a chalkboard. Each “YOU” leads to a different outcome, but it’s unclear exactly how many adventures there actually are. One outcome reads, “This is a song sung only for you. When you was not yet you. What I was not yet I. When I was still you. When you were the song.” Another outcome reads “You have shattered” and then cuts quickly to a bright pink screen filled with zeros and parentheses.

Comfort zone (2021) by Sorawit features footage of kōtuku (white heron) nesting sites in South Westland. Common in Asia, kōtuku have only one known nesting site in Aotearoa. Sorawit’s footage of this comparatively rare bird is interspersed with digital drawings of kōtuku and 3D animations of bridges that are overlaid with interview-style narration. Continuing Sorawit’s interest in interrogating ecological histories, Comfort zone honours kōtuku in Aotearoa. Similarly set in nature, Laura’s what lives in the lacunae? (2022), offers a darkly fantastical night-time forest populated by freakish elven characters. Donning bleach-blond wigs, pointed ears, and red contact lenses, these characters roam the night in a Mulholland Drive kind of darkness. This allusion is amplified by my own sapphic reading of the work, but the manic laughter of the characters sans audio feels joyfully Lynchian.

Curatorially, the works are divided into two groupings. The first grouping — titled Glancing into the wilderness— includes works by Aliyah, Sorawit and Laura that “evoke disruption and rupture the very fabric of reality.”1 The visitor is greeted by Aliyah’s restoration fibre song (2022), a poetic text-based ‘choose your own adventure’ type game controlled by an ergonomic mouse on a metallic silver-surfaced table. On a black screen, the sentence, “You wake up, swathed in white cloth” appears in white and purple text, with the purple indicating clickable options. The visitor clicks through until they reach a screen with the word “YOU” in purple, repeated multiple times like lines on a chalkboard. Each “YOU” leads to a different outcome, but it’s unclear exactly how many adventures there actually are. One outcome reads, “This is a song sung only for you. When you was not yet you. What I was not yet I. When I was still you. When you were the song.” Another outcome reads “You have shattered” and then cuts quickly to a bright pink screen filled with zeros and parentheses.

Comfort zone (2021) by Sorawit features footage of kōtuku (white heron) nesting sites in South Westland. Common in Asia, kōtuku have only one known nesting site in Aotearoa. Sorawit’s footage of this comparatively rare bird is interspersed with digital drawings of kōtuku and 3D animations of bridges that are overlaid with interview-style narration. Continuing Sorawit’s interest in interrogating ecological histories, Comfort zone honours kōtuku in Aotearoa. Similarly set in nature, Laura’s what lives in the lacunae? (2022), offers a darkly fantastical night-time forest populated by freakish elven characters. Donning bleach-blond wigs, pointed ears, and red contact lenses, these characters roam the night in a Mulholland Drive kind of darkness. This allusion is amplified by my own sapphic reading of the work, but the manic laughter of the characters sans audio feels joyfully Lynchian.

Aliyah Winter, restoration fibre song, 2022 (still).

Sorawit Songsataya, Comfort zone, 2021 (still). Video. Voice by Awa Puna (Ngāti Kahungunu ki Wairoa). 10 mins.

Laura Duffy, what lives in the lacunae?, 2022 (still). Video. 15 mins 20 secs.

Sorawit Songsataya, Comfort zone, 2021 (still). Video. Voice by Awa Puna (Ngāti Kahungunu ki Wairoa). 10 mins.

Laura Duffy, what lives in the lacunae?, 2022 (still). Video. 15 mins 20 secs.

The second grouping, titled Viewing the undercommons, links Niehana, Connor, and Dan’s works which collectively examine the camera as an apparatus: as a tool for both representation and exposure. Neihana’s You are a Star (2022) completes his Queer praxis trilogy (following I like this queer scene but I’ve slept with both of them, 2017, and Congrats on your versatility, 2019). Possibly incorporating Neihana’s community work with Rainbow Youth for the first time, You are a Star focuses on issues of housing insecurity affecting takatāpui youth in Aotearoa. Told through the friendship between two characters, the straightforward narrative approach feels very like a short film. However this comment isn’t intended as a critique. In my conversation with Neihana and Dan for the CIRCUIT podcast, both spoke of the frustration of the “gay tragedy” trope that exists in film and media. You are a Star continues Neihana’s use of humour and lightness to counter this mode of storytelling and, in this instance, is charming in its earnestness.

Also on the subject of friendship and similarly earnest is Connor’s Love Letter (2022). Following her feature length work Towards the Sun (2021), shown as part of Artspace’s annual new artists show Cruel Optimism, Love Letter is a similarly long-form film. More atmospheric than narrative, the work follows a weekend trip away with friends capturing moments of intimate playfulness. According to the exhibition text, the work is quite literally a love letter to friends, and positions friendship as an issue of trans safety. Dan’s Queen of the round table (2022) employs a documentary style of filming, the subject of which is a queer activist. Dan follows them around their abundantly decorated house with the camera as they discuss their activism work and morbidly rehearse their own funeral. The film ends with an at-home karaoke rendition of What a Difference a Day Makes. Queen of the round table aims to hand over autonomy to its subject; to direct the director.

Also on the subject of friendship and similarly earnest is Connor’s Love Letter (2022). Following her feature length work Towards the Sun (2021), shown as part of Artspace’s annual new artists show Cruel Optimism, Love Letter is a similarly long-form film. More atmospheric than narrative, the work follows a weekend trip away with friends capturing moments of intimate playfulness. According to the exhibition text, the work is quite literally a love letter to friends, and positions friendship as an issue of trans safety. Dan’s Queen of the round table (2022) employs a documentary style of filming, the subject of which is a queer activist. Dan follows them around their abundantly decorated house with the camera as they discuss their activism work and morbidly rehearse their own funeral. The film ends with an at-home karaoke rendition of What a Difference a Day Makes. Queen of the round table aims to hand over autonomy to its subject; to direct the director.

Neihana Gordon-Stables, You are a Star, 2022 (still). Video. 5 mins 45 secs.

Connor Fitzgerald, Love Letter, 2022 (still). Video. 53 mins.

Daniel John Corbett Sanders, Queen of the round table, 2022 (still). Video. 10 mins 6 secs.

Connor Fitzgerald, Love Letter, 2022 (still). Video. 53 mins.

Daniel John Corbett Sanders, Queen of the round table, 2022 (still). Video. 10 mins 6 secs.

Both the podcast series and the exhibition Wild Once More group these artists under broad and, at times, problematic categories of sexuality and gender identities. While there are certain links and commonalities between the artists’ practices and works, their work can also be framed through other vectors, such as age or class or race. And I think this is a key point: to explore the limitations of categorisation. In an interview titled Friendship as a Way of Life, Michel Foucault says:

Following Foucault, the artists’ works in Wild Once More refuse the task of unearthing an inherent “queer truth” to focus instead on the relations we have to each other and our environments. In the same interview, Foucault argues that this queer relationality, and in particular queer modes of friendship, are most threatening to the heterosexual institution. And for me, it is these friendships that I find most exciting about Wild Once More. For me personally, there are entry points to these works that are available only via intimacy, such as seeing Neihana’s own house being used as a film set or recognising Laura and our mutual friend, Jelly, playing dress up as goblin freaks—there are moments here that are just for friends.

Wild Once More, curated by Christopher Ulutupu, 2022. Artists: Aliyah Winter, Connor Fitzgerald, Daniel John Corbett Sanders, Laura Duffy, Neihana Gordon-Stables, Sorawit Songsatay. March 03 – 27 2022, Te Tuhi, Ōtautahi.

Images courtesy of the artists and Te Tuhi. All works except Comfort zone were commissioned by Te Tuhi for Wild Once More.

![]()

Article image: Wild Once More, 2022 (installation view). Curated by Christopher Ulutupu. Work by Aliyah Winter. Photo by Sam Hartnett.

1. Christopher Ulutupu, Wild Once More, 2022. https://tetuhi.art/art-archive/digital-library/read/wild-once-more/

2. Michel Foucault, Ethics: Subjectivity and Truth, 1994. New York, NY: The New Press. P. 135.

Another thing to distrust is the tendency to relate the question of homosexuality to the problem of “Who am I?” and “What is the secret of my desire?” Perhaps it would be better to ask oneself, “‘What relations, through homosexuality, can be established, invented, multiplied, and modulated?” The problem is not to discover in oneself the truth of one’s sex, but, rather, to use one’s sexuality henceforth to arrive at a multiplicity of relationships.2

Following Foucault, the artists’ works in Wild Once More refuse the task of unearthing an inherent “queer truth” to focus instead on the relations we have to each other and our environments. In the same interview, Foucault argues that this queer relationality, and in particular queer modes of friendship, are most threatening to the heterosexual institution. And for me, it is these friendships that I find most exciting about Wild Once More. For me personally, there are entry points to these works that are available only via intimacy, such as seeing Neihana’s own house being used as a film set or recognising Laura and our mutual friend, Jelly, playing dress up as goblin freaks—there are moments here that are just for friends.

Wild Once More, curated by Christopher Ulutupu, 2022. Artists: Aliyah Winter, Connor Fitzgerald, Daniel John Corbett Sanders, Laura Duffy, Neihana Gordon-Stables, Sorawit Songsatay. March 03 – 27 2022, Te Tuhi, Ōtautahi.

Images courtesy of the artists and Te Tuhi. All works except Comfort zone were commissioned by Te Tuhi for Wild Once More.

Article image: Wild Once More, 2022 (installation view). Curated by Christopher Ulutupu. Work by Aliyah Winter. Photo by Sam Hartnett.

1. Christopher Ulutupu, Wild Once More, 2022. https://tetuhi.art/art-archive/digital-library/read/wild-once-more/

2. Michel Foucault, Ethics: Subjectivity and Truth, 1994. New York, NY: The New Press. P. 135.

ISSN 2744-7952

Thank you for reading ︎

Vernacular logo designed by Yujin Shin

vernacular.criticism ︎