Still, pictures

A response to Geist by Tessa Ayling-Guhl

Geist | Tessa Ayling-Guhl | Hunters and Collectors, Pōneke

17.08.23 | written by Jess Clifford

“Everything exists to end in a photograph.”

Susan Sontag, On Photography (1977)

“Photography is also an act of love.”

Hervé Guibert, Ghost Image (1981)

In Ghost Dance, his 2006 autobiography of sorts, Douglas Wright recalls his earliest memory, “so faint it’s almost an apparition.” He writes, “I was pressing my forehead up against the cold glass of our lounge window watching a lady in a long white gown on the verandah of the house opposite. She was dancing back and forth, her white dress fluttering like the wings of a moth. The memory is dreamlike, soundless—just the moth lady fluttering back and forth in my mind.”1 A visionary artist, dancer and choreographer, this moment of encounter with dance might seem like the very first in which Wright glimpsed, however faintly, his lifelong vocation. And yet he gives no further context, the image drifts; we too are left with just this presence, fluttering back and forth in our minds. Reading this passage, Wright’s memory calls up the hazy, ineffable apparitions of the photographer Francesca Woodman, her own “dreamlike, soundless” self-portraits in which the artist appears as a kind of ghostly invocation, a quivering vibration in the image. Here we find the artist’s presence bound in black and white. I think of the way writer Larissa Pham describes the alchemical process of a photograph’s transformation, of the way the image rises up. “Slowly, as if by magic, an image appear[s] out of the fog, areas darkening and resolving into line, form, and shape… The texture of it sumptuous, the fine grain of silver nitrate, shiny under wet chemicals … its oily sheen.”2

So here Wright’s very first memory acts like a photographic negative, a textured surface onto which to project the traces of things thought and felt. In his words, I hear the echo of the affective friendships between artists and writers that could be described as photographic—Douglas Wright and Tessa Ayling-Guhl in Aotearoa, Hervé Guibert and Michel Foucault in Paris, David Wojnarovicz and Peter Hujar in New York. It's a kind of entangled vision, a weaving together of lives and images (of memory and death), to draw lines and create overlays between multiplicities.

So here Wright’s very first memory acts like a photographic negative, a textured surface onto which to project the traces of things thought and felt. In his words, I hear the echo of the affective friendships between artists and writers that could be described as photographic—Douglas Wright and Tessa Ayling-Guhl in Aotearoa, Hervé Guibert and Michel Foucault in Paris, David Wojnarovicz and Peter Hujar in New York. It's a kind of entangled vision, a weaving together of lives and images (of memory and death), to draw lines and create overlays between multiplicities.

Of memory and death. Because we’re talking about the plague years—as literary scholar and AIDS historian Sarah Shulman puts it, “The years from 1981 to 1996, when there was a mass death experience of young people. Where folks my age watched in horror as our friends, their lovers, cultural heroes, influences, buddies, the people who witnessed our lives as we witnessed theirs, as these folks sickened and died consistently for fifteen years.” Her irony worn wan, she asks, “Have you heard about it?”3

I’m introduced to Douglas Wright’s work by a performance artist with whom I’m working on another project, an exhibition centred around the novel To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life by French writer and photographer Hervé Guibert.4 Written following Guibert’s terminal AIDS diagnosis in late 1980s Paris, his narrative is a loose fiction of three months in the penultimate year of the author’s life. The book is most widely known for its tender, candid account of the death of the narrator’s friend Muzil—a stand-in for the inimitable philosopher and BDSM enthusiast Michel Foucault. Upon its publication, Foucault was outed to French media twice-over, for his sexual appetites, and, as dying from AIDS. The younger Guibert was Foucault’s neighbour; the pair’s close bond—intense, paternalistic, platonic—was well known throughout the Venn diagram of Paris’s literary and leather circles. In one scene in To the Friend, the narrator recalls a gift from Muzil of Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations, which opens with “a text praising his elders, different members of his family, his teachers, in which he thanked each person in particular, the dead first of all, for what they had taught him and the way they had changed his life for the better.” As Guibert continues, “Muzil, who was to die a few months later, remarked that he planned to write something similar soon about me—and I wondered how I could have ever managed to teach him anything.”5

Published in French as À l’ami qui ne m’a sauvé la vie, in its gallic construction, Guibert’s title is estranged from his authoring body, the life—la vie—is removed from its presumptive owner. French does not say save my life, it can only say the life, in the way that we might say that friendship saves lives beyond any singular pairing. In his book, Friendship as a Way of Life: Foucault, AIDS, and the Politics of Shared Estrangement, the cultural historian Tom Roach opens a chapter on Foucault and Guibert with an interpretation of the power of friendship by the philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari. He writes: “A concept is created in the intellectual interstices of two philosophers, two friends. It is not rightfully their concept, of course, it is, as Deleuze and Guattari note, their friend, the doubling (even quadrupling) of their friendship. The property of neither, the potentiality of both, the concept emerges as a third term between two.”6 Which is to say, it is in the interstices of two minds, two oeuvres—as when silver meets light—that the magic happens.

In To the Friend, it is precisely friendship (and their shared seropositive status) that allows Hervé, as unnamed narrator, to act as witness to Muzil’s death, and then to write it all down: He says, “The next day, alone with Muzil, I held his hand for a long time, the way I sometimes had in his apartment when we used to sit side by side on his white couch, while the sun slowly set, framed by French windows standing wide open in the summer air. Then I pressed my lips to his hand in a kiss.” Plagued by doubt, he has a revelation:

One of Guibert’s most well-known photographs is titled L’ami (the friend) (1980). It welcomed visitors into the Galerie Agathe Gaillard in 1984, where Guibert exhibited the series that would become his first book of photography, Le seul visage (The only face). It is the first photo in that book.8 L’ami depicts a man’s shirtless torso, chest and shoulders that dominate the frame. Another hand reaches out from the bottom-left corner. Its palm touches the man’s bare skin, fingers reaching sternum, deep shadows forming in its imprint. As is characteristic of Guibert’s photography, L’ami is shot in black and white, with a strong emphasis on the interplay of shadow and light. The majority of the image is out of focus: two spectral bodies enact a gesture of ambiguous caress and recede into shadow.

![]()

When the photographer Peter Hujar died in 1987 of AIDs-related pneumonia, his friend and former lover David Wojnarowicz was with him. In Close to the Knives: A Memoir of Disintegration, Wojnarowicz describes the experience of witnessing Hujar’s death, writing how his first instinct was to grab his Super 8 camera and record “his open eye, his open mouth, that beautiful hand with the hint of gauze at the wrist that held the IV needle, the colour of his hand like marble, the full sense of the flesh of it.”9 He writes of the stillness, the impossibility of trying to capture the light he had seen in Hujar’s eyes, now gone. He films a sweep of Hujar’s body, then takes twenty-three photographs of his face, feet, and hands (the number is a recurring theme in Wojnarowicz’s work). Hujar’s just-departed presence haunts these images; eyelids appear to flutter, his lips are parted, breath elapsed. There’s an uncanny parallel with a series of portraits of David Wojnarowicz Reclining taken by Hujar in 1981, a sort of foreshadowing. The later photographs are an act of the utmost intimacy—laid bare in the simplest of compositions—friendship in its purest form. Wojnarowicz would himself die three years later, full of as much tenderness and rage as on that day. “I took a last swig from my beer, overcome with the sensations of touch, of my fingers and palms smoothing along some untouched body in some imagined and silent sun-filled room.”10

I’m introduced to Douglas Wright’s work by a performance artist with whom I’m working on another project, an exhibition centred around the novel To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life by French writer and photographer Hervé Guibert.4 Written following Guibert’s terminal AIDS diagnosis in late 1980s Paris, his narrative is a loose fiction of three months in the penultimate year of the author’s life. The book is most widely known for its tender, candid account of the death of the narrator’s friend Muzil—a stand-in for the inimitable philosopher and BDSM enthusiast Michel Foucault. Upon its publication, Foucault was outed to French media twice-over, for his sexual appetites, and, as dying from AIDS. The younger Guibert was Foucault’s neighbour; the pair’s close bond—intense, paternalistic, platonic—was well known throughout the Venn diagram of Paris’s literary and leather circles. In one scene in To the Friend, the narrator recalls a gift from Muzil of Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations, which opens with “a text praising his elders, different members of his family, his teachers, in which he thanked each person in particular, the dead first of all, for what they had taught him and the way they had changed his life for the better.” As Guibert continues, “Muzil, who was to die a few months later, remarked that he planned to write something similar soon about me—and I wondered how I could have ever managed to teach him anything.”5

Published in French as À l’ami qui ne m’a sauvé la vie, in its gallic construction, Guibert’s title is estranged from his authoring body, the life—la vie—is removed from its presumptive owner. French does not say save my life, it can only say the life, in the way that we might say that friendship saves lives beyond any singular pairing. In his book, Friendship as a Way of Life: Foucault, AIDS, and the Politics of Shared Estrangement, the cultural historian Tom Roach opens a chapter on Foucault and Guibert with an interpretation of the power of friendship by the philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari. He writes: “A concept is created in the intellectual interstices of two philosophers, two friends. It is not rightfully their concept, of course, it is, as Deleuze and Guattari note, their friend, the doubling (even quadrupling) of their friendship. The property of neither, the potentiality of both, the concept emerges as a third term between two.”6 Which is to say, it is in the interstices of two minds, two oeuvres—as when silver meets light—that the magic happens.

In To the Friend, it is precisely friendship (and their shared seropositive status) that allows Hervé, as unnamed narrator, to act as witness to Muzil’s death, and then to write it all down: He says, “The next day, alone with Muzil, I held his hand for a long time, the way I sometimes had in his apartment when we used to sit side by side on his white couch, while the sun slowly set, framed by French windows standing wide open in the summer air. Then I pressed my lips to his hand in a kiss.” Plagued by doubt, he has a revelation:

And then I sensed—it’s extraordinary—a kind of vision, or vertigo, that gave me complete authority, putting me in charge of these ignoble transcripts and legitimizing them by revealing to me (so it was what’s called a premonition, a powerful presentiment) that I was completely entitled to do this since it wasn’t so much my friend’s last agony I was describing as it was my own, which was waiting for me and would be just like his, for it was now clear that besides being bound by friendship, we would share the same fate in death.7

One of Guibert’s most well-known photographs is titled L’ami (the friend) (1980). It welcomed visitors into the Galerie Agathe Gaillard in 1984, where Guibert exhibited the series that would become his first book of photography, Le seul visage (The only face). It is the first photo in that book.8 L’ami depicts a man’s shirtless torso, chest and shoulders that dominate the frame. Another hand reaches out from the bottom-left corner. Its palm touches the man’s bare skin, fingers reaching sternum, deep shadows forming in its imprint. As is characteristic of Guibert’s photography, L’ami is shot in black and white, with a strong emphasis on the interplay of shadow and light. The majority of the image is out of focus: two spectral bodies enact a gesture of ambiguous caress and recede into shadow.

When the photographer Peter Hujar died in 1987 of AIDs-related pneumonia, his friend and former lover David Wojnarowicz was with him. In Close to the Knives: A Memoir of Disintegration, Wojnarowicz describes the experience of witnessing Hujar’s death, writing how his first instinct was to grab his Super 8 camera and record “his open eye, his open mouth, that beautiful hand with the hint of gauze at the wrist that held the IV needle, the colour of his hand like marble, the full sense of the flesh of it.”9 He writes of the stillness, the impossibility of trying to capture the light he had seen in Hujar’s eyes, now gone. He films a sweep of Hujar’s body, then takes twenty-three photographs of his face, feet, and hands (the number is a recurring theme in Wojnarowicz’s work). Hujar’s just-departed presence haunts these images; eyelids appear to flutter, his lips are parted, breath elapsed. There’s an uncanny parallel with a series of portraits of David Wojnarowicz Reclining taken by Hujar in 1981, a sort of foreshadowing. The later photographs are an act of the utmost intimacy—laid bare in the simplest of compositions—friendship in its purest form. Wojnarowicz would himself die three years later, full of as much tenderness and rage as on that day. “I took a last swig from my beer, overcome with the sensations of touch, of my fingers and palms smoothing along some untouched body in some imagined and silent sun-filled room.”10

The more you look for something, the more you find it. I begin to find myself enmeshed in a spiralling confluence of references—to artists, their lives and work. I’m reading Ghost Dance when I learn about a forthcoming exhibition by the Te Whanganui-a-Tara-based photographer Tessa Ayling-Guhl, of a series of portraits of Douglas Wright that she took at his home in Mt Eden in 2015—at what proved to be their only meeting. I mention this to an artist friend in Paris; he agrees. “It’s all very Hegelian,” he says (he’s Swiss, naturally), then laughs upon learning that the exhibition is to be called Geist. Largely untranslatable from German, the term Geist contains the English meanings of ghost, spirit, mind, and intellect in one—and in so doing encapsulates a person’s essence, the elemental quality of the body as well as its fallibility. Its compound, Zeitgeist, to be of the moment, is itself a concept distinctly related to the German philosopher Hegel’s view of history in which each successive epoch reveals its true essence of spirit.

These days, it is of the moment to think and talk about the precarity of working in the artworld, our etiolated relationship to notions of stability and job security. And yet I also think of this shared sense of vocation that tethers us together, how friendships sustain each other along this winding path. As Ayling-Guhl says of seeing a performance of Black Milk (2006) as a teenager: “It cracked my mind open creatively, viscerally, and emotionally. That was a pivotal moment in my own mind's creation.”11 Or as Cartier-Bresson would say of that instant captured by the camera, the decisive moment.

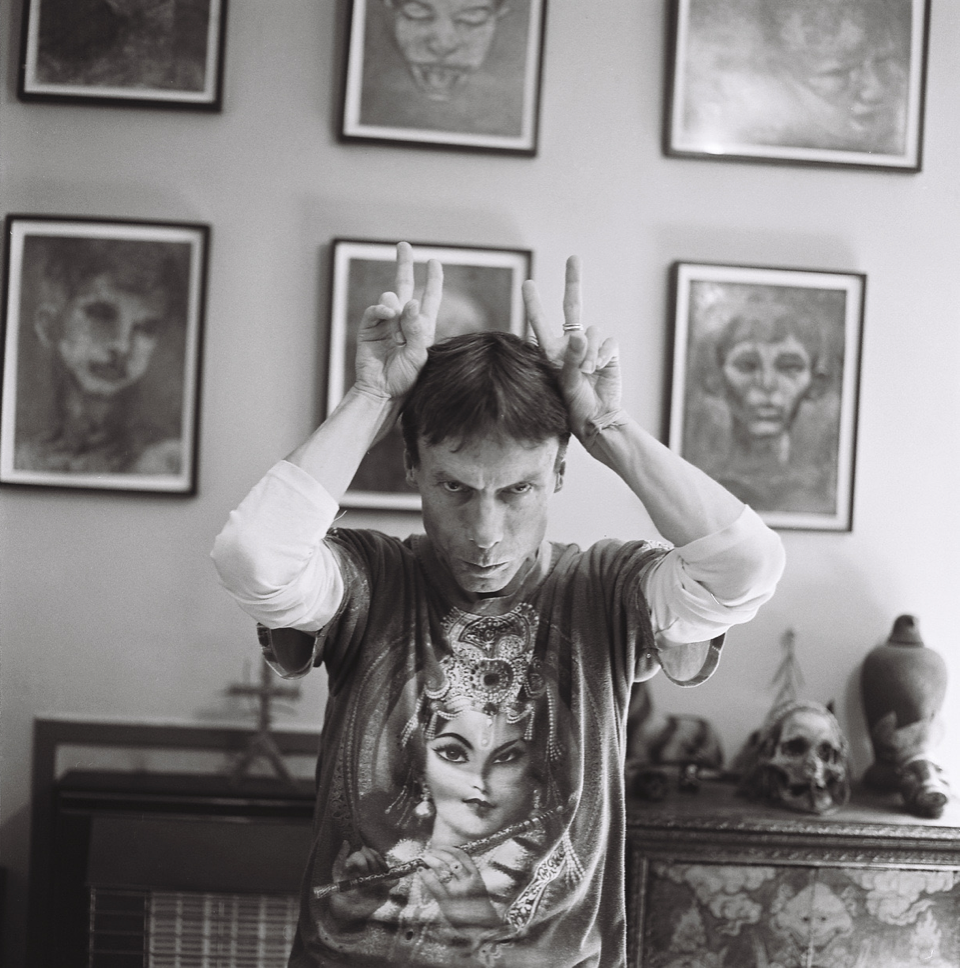

I’m watching the 2003 documentary Haunting Douglas, which includes a recording of Wright performing his work Elegy (1993). Here, Wright’s body is lithe, muscular, powerful. Watching him dance, what strikes me is this certain inner quality that’s always coming to the surface. I don’t know what to call it. Exhilaration, grace, animal spirits. It makes him seem more alive than others, somehow. It’s hard to stop looking. Over a decade later, caught in Ayling-Guhl’s photographs, Wright is a body in motion—fleeting, evanescent. He dances in his luscious sub-tropical garden and in his “silent sun-filled” living room, surrounded by the artworks of his former lover and lifelong confidante, Malcolm Ross. (While there is not adequate space here, Ross had his own elliptical relationship to photography and a compulsive, proleptic fatalism to rival Guibert’s.) Shot on a medium-format camera, these images enact a kind of dialogic address—she’s speaking in the medium. I think of how artist Moyra Davey writes of her continued use of analogue photography. For Davey, its materiality is discursive:

A negative carries all the details that the light has seen. There is an unmistakably elegiac quality to these pictures: Wright is full of life, the moment suspended in photography. They hold still what Susan Sontag calls “time’s relentless melt.”13 Like in Guibert, Hujar and Wojnarowicz’s own images, they fix those close moments between artist and photographer, and will continue to do so over days innumerable. There’s a harrowing account of Wright’s HIV diagnosis, which he received in 1990, on the first page of Ghost Dance. As he describes it: “For years I felt we were climbing, in single file, a steep and narrow staircase which led to a platform over a bottomless pit, and we were pressed so hard from behind that once at the front you had no choice but to jump or be pushed.”14 Given a brief reprieve by advances in treatment, Wright passed away in 2018, aged 62, from cancer.

![]()

In semiotics, as those who are disciplined might know, photography is the only medium that betrays its indexical relationship to source—the thing that the image represents is also the root cause of its material apparition. So photography is an art and a history of intimacy, a register of touch, of gaze, of fingers outstretched to seek flesh.

Phōtos, from the Greek, meaning “light,” and graphé, meaning “representation by means of lines,” from which we get photography—to draw with light.

With light, as with longing.

In a text entitled Black and White Photos (To Hervé Guibert), the artist and poet Sholto Buck limns a beatific portrait of Guibert: “Head tilted to the side, gaze cast upwards. Your eyes are languid and wide. Your hair is curly. Your lips are lips I’d like to kiss.”15 These are lips that kissed Muzil’s cold hand. How the image rises up.

By touch, through touch. As witness, as mirror. As mourning.

1. Douglas Wright, Ghost Dance. Auckland: Penguin Books, 2004, p. 154.

2. Larissa Pham, Pop Songs: Adventures in Art and Intimacy. New York: Catapult, 2021, p. 105.

3. Sarah Shulman, The Gentrification of the Mind: Witness to a Lost Imagination. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013, p. 45

4. Originally published as Hervé Guibert, À l'ami qui ne m'a pas sauvé la vie. Paris: Gallimard, 1990.

5. Hervé Guibert, To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life. London: Serpent’s Tail, 2021, pp. 74-75.

6. Tom Roach, Friendship as a Way of Life: Foucault, AIDS, and the Politics of Shared Estrangement. New York: SUNY Press, 2012, p. 1.

7. Hervé Guibert, To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life. London: Serpent’s Tail, 2021, pp. 98-99.

8. Tom Roach, Friendship as a Way of Life: Foucault, AIDS, and the Politics of Shared Estrangement. New York: SUNY Press, 2012, p. 2.

9. David Wojnarowicz, Close to the Knives: A Memoir of Disintegration. Edinburgh: Canongate, 2016, pp. 111-12. The book is dedicated to Peter Hujar, Tom Rauffenbart and Marion Scemama.

10. Ibid.

11. Tessa Ayling-Guhl, quoted in the Geist exhibition text, 2023, n.p.

12. Moyra Davey, Two Hot Horses. Vancouver: Filip, 2022, p. 3.

13. Susan Sontag, On Photography (1977), quoted in Larissa Pham, Pop Songs: Adventures in Art and Intimacy. New York: Catapult, 2021, p. 121.

14. Douglas Wright, Ghost Dance. Auckland: Penguin Books, 2004, p. 15.

15. Sholto Buck, ‘BLACK AND WHITE PHOTOS (To Hervé Guibert),’ 2020, n.p. https://mayfairartfair.com/artists/sholto-buck/

![]()

All photos: Tessa Ayling-Guhl, Untitled (Douglas Wright), 2015, printed 2023. Courtesy of the artist.

Tessa Ayling-Guhl, Geist, 2023, at Hunters and Collectors, Pōneke. 5 May – 29 May 2023.

These days, it is of the moment to think and talk about the precarity of working in the artworld, our etiolated relationship to notions of stability and job security. And yet I also think of this shared sense of vocation that tethers us together, how friendships sustain each other along this winding path. As Ayling-Guhl says of seeing a performance of Black Milk (2006) as a teenager: “It cracked my mind open creatively, viscerally, and emotionally. That was a pivotal moment in my own mind's creation.”11 Or as Cartier-Bresson would say of that instant captured by the camera, the decisive moment.

I’m watching the 2003 documentary Haunting Douglas, which includes a recording of Wright performing his work Elegy (1993). Here, Wright’s body is lithe, muscular, powerful. Watching him dance, what strikes me is this certain inner quality that’s always coming to the surface. I don’t know what to call it. Exhilaration, grace, animal spirits. It makes him seem more alive than others, somehow. It’s hard to stop looking. Over a decade later, caught in Ayling-Guhl’s photographs, Wright is a body in motion—fleeting, evanescent. He dances in his luscious sub-tropical garden and in his “silent sun-filled” living room, surrounded by the artworks of his former lover and lifelong confidante, Malcolm Ross. (While there is not adequate space here, Ross had his own elliptical relationship to photography and a compulsive, proleptic fatalism to rival Guibert’s.) Shot on a medium-format camera, these images enact a kind of dialogic address—she’s speaking in the medium. I think of how artist Moyra Davey writes of her continued use of analogue photography. For Davey, its materiality is discursive:

I want to make the kind of object that traces its roots back to the storytelling invoked by philosopher Walter Benjamin in his essay ‘Little History of Photography,’ where he says that photographers are “descendent[s] of the augurs and haruspices”: those who spin tales and divine the future from animal entrails. It’s continuity with that narrative that I want to hold on to, as well as the link with a materiality derived from solar rays and mineral compounds.12

A negative carries all the details that the light has seen. There is an unmistakably elegiac quality to these pictures: Wright is full of life, the moment suspended in photography. They hold still what Susan Sontag calls “time’s relentless melt.”13 Like in Guibert, Hujar and Wojnarowicz’s own images, they fix those close moments between artist and photographer, and will continue to do so over days innumerable. There’s a harrowing account of Wright’s HIV diagnosis, which he received in 1990, on the first page of Ghost Dance. As he describes it: “For years I felt we were climbing, in single file, a steep and narrow staircase which led to a platform over a bottomless pit, and we were pressed so hard from behind that once at the front you had no choice but to jump or be pushed.”14 Given a brief reprieve by advances in treatment, Wright passed away in 2018, aged 62, from cancer.

In semiotics, as those who are disciplined might know, photography is the only medium that betrays its indexical relationship to source—the thing that the image represents is also the root cause of its material apparition. So photography is an art and a history of intimacy, a register of touch, of gaze, of fingers outstretched to seek flesh.

Phōtos, from the Greek, meaning “light,” and graphé, meaning “representation by means of lines,” from which we get photography—to draw with light.

With light, as with longing.

In a text entitled Black and White Photos (To Hervé Guibert), the artist and poet Sholto Buck limns a beatific portrait of Guibert: “Head tilted to the side, gaze cast upwards. Your eyes are languid and wide. Your hair is curly. Your lips are lips I’d like to kiss.”15 These are lips that kissed Muzil’s cold hand. How the image rises up.

By touch, through touch. As witness, as mirror. As mourning.

1. Douglas Wright, Ghost Dance. Auckland: Penguin Books, 2004, p. 154.

2. Larissa Pham, Pop Songs: Adventures in Art and Intimacy. New York: Catapult, 2021, p. 105.

3. Sarah Shulman, The Gentrification of the Mind: Witness to a Lost Imagination. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013, p. 45

4. Originally published as Hervé Guibert, À l'ami qui ne m'a pas sauvé la vie. Paris: Gallimard, 1990.

5. Hervé Guibert, To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life. London: Serpent’s Tail, 2021, pp. 74-75.

6. Tom Roach, Friendship as a Way of Life: Foucault, AIDS, and the Politics of Shared Estrangement. New York: SUNY Press, 2012, p. 1.

7. Hervé Guibert, To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life. London: Serpent’s Tail, 2021, pp. 98-99.

8. Tom Roach, Friendship as a Way of Life: Foucault, AIDS, and the Politics of Shared Estrangement. New York: SUNY Press, 2012, p. 2.

9. David Wojnarowicz, Close to the Knives: A Memoir of Disintegration. Edinburgh: Canongate, 2016, pp. 111-12. The book is dedicated to Peter Hujar, Tom Rauffenbart and Marion Scemama.

10. Ibid.

11. Tessa Ayling-Guhl, quoted in the Geist exhibition text, 2023, n.p.

12. Moyra Davey, Two Hot Horses. Vancouver: Filip, 2022, p. 3.

13. Susan Sontag, On Photography (1977), quoted in Larissa Pham, Pop Songs: Adventures in Art and Intimacy. New York: Catapult, 2021, p. 121.

14. Douglas Wright, Ghost Dance. Auckland: Penguin Books, 2004, p. 15.

15. Sholto Buck, ‘BLACK AND WHITE PHOTOS (To Hervé Guibert),’ 2020, n.p. https://mayfairartfair.com/artists/sholto-buck/

All photos: Tessa Ayling-Guhl, Untitled (Douglas Wright), 2015, printed 2023. Courtesy of the artist.

Tessa Ayling-Guhl, Geist, 2023, at Hunters and Collectors, Pōneke. 5 May – 29 May 2023.

ISSN 2744-7952

Thank you for reading ︎

Vernacular logo designed by Yujin Shin

vernacular.criticism ︎