Communication breakdown

A response to October 1935 by Aliyah Winter

October 1935 | Aliyah Winter | RM, Tāmaki Makaurau

07.05.23 | written by Divyaa Kumar

October 1935 by Aliyah Winter is a deceptively simple yet incredibly layered exhibition. Hosted by RM Gallery in Tāmaki Makaurau, the show explores the mechanics of communication, how we speak to one another, of one another, what we can speak and write about, and the inherent limitations of language. For many queer folk, the un/covering of language draws a complex cartography of linguistic connections, often circumnavigating conventional speech.

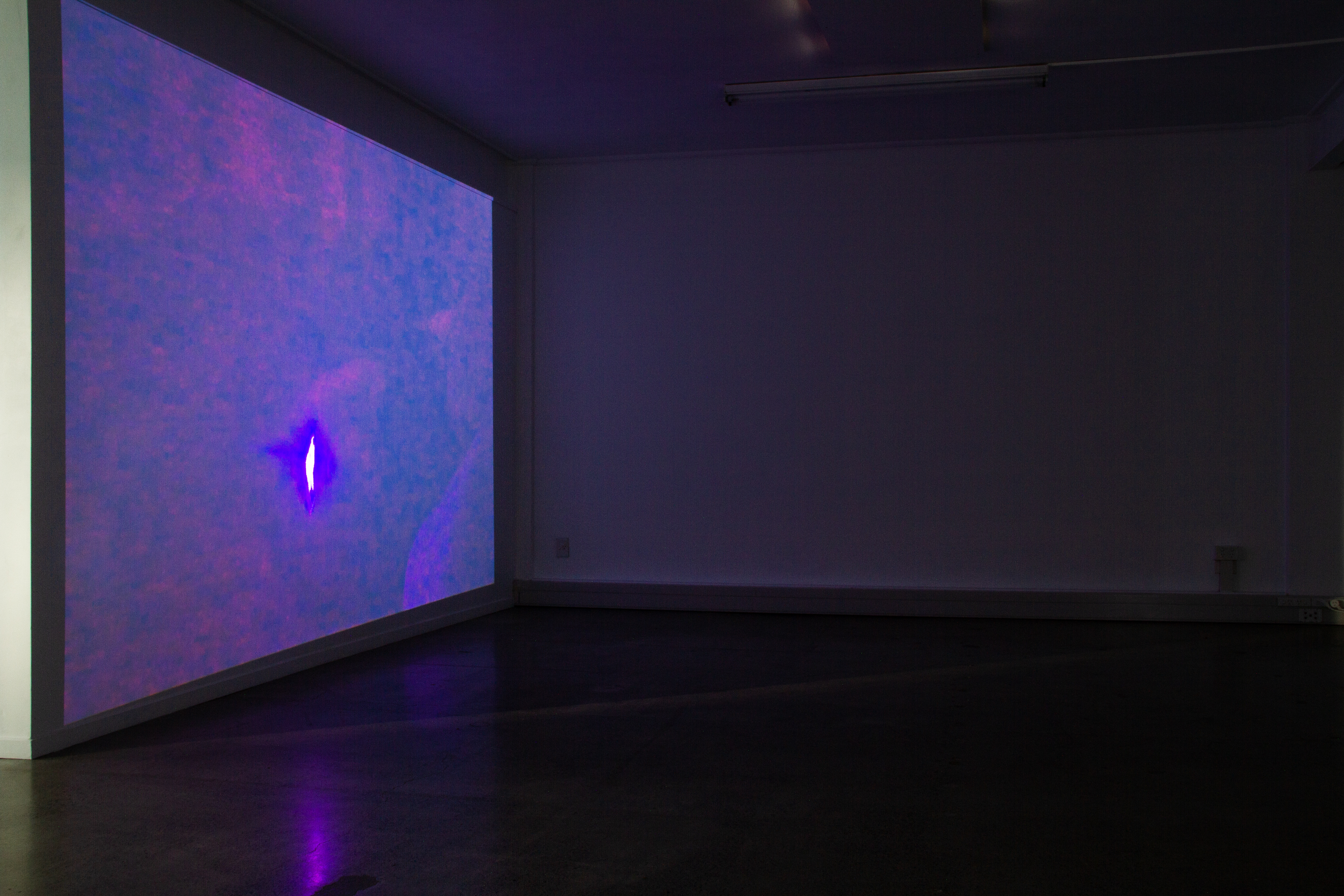

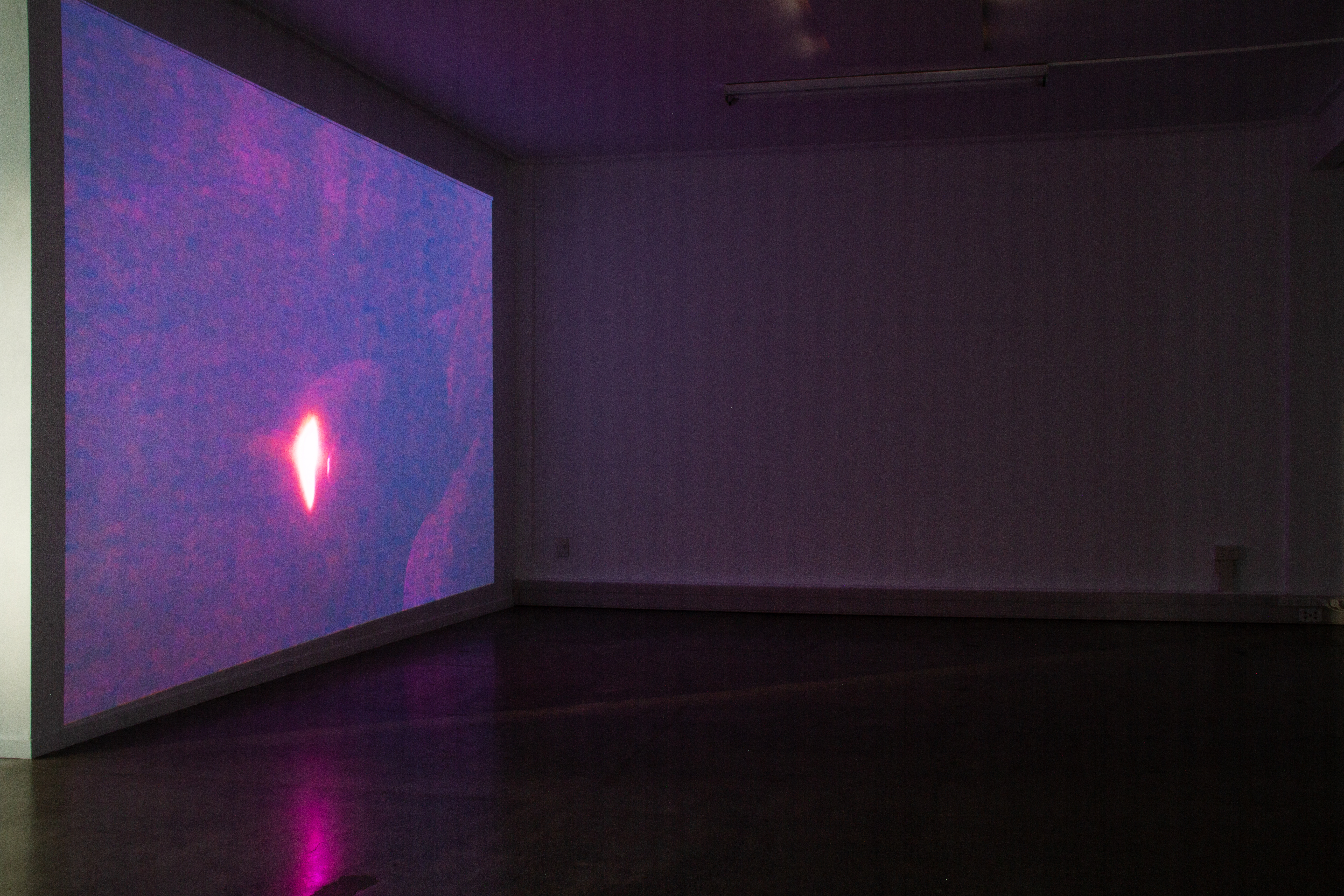

The exhibition itself occupies the first of the two rooms the gallery is separated into, being the first work you see once you’ve scaled the narrow staircase. Projected onto the shared dividing wall, fully covering the expanse of the wall, is a dark video that pusles between obfuscating blurriness to a semi-legible focus. Slowly toggling between the two ends of the camera’s focus, the frame remains unmoving on a face draped in shadows, illuminated only by a hot pink light emanating from the (presumably artist’s) mouth. This light escapes from the mouth as the figure speaks, but is also visible when they aren’t talking, able to be seen in the darkness through the seam of their mouth.

The exhibition itself occupies the first of the two rooms the gallery is separated into, being the first work you see once you’ve scaled the narrow staircase. Projected onto the shared dividing wall, fully covering the expanse of the wall, is a dark video that pusles between obfuscating blurriness to a semi-legible focus. Slowly toggling between the two ends of the camera’s focus, the frame remains unmoving on a face draped in shadows, illuminated only by a hot pink light emanating from the (presumably artist’s) mouth. This light escapes from the mouth as the figure speaks, but is also visible when they aren’t talking, able to be seen in the darkness through the seam of their mouth.

The sound that plays with this video is intentionally muffled and indistinct. It reverberates in the space through the small speakers at the rear of the room, and the concrete floors provide an echo that lingers like a computer lag, adding this likely unintentional but endearing disconnect with the moving mouth. We cannot know what exactly is being said, but as the video sharpens, so does the decipherability of the audio. This visual and auditory darkness suggests a deliberate communication boundary.

It is simple, yet remarkably complex. It takes several watches, each differently considered, and a few conversations with friends to unpack even a fraction of what is being presented. There is no floor sheet, only a small stack of waxy greige pages with the titular poem typed up. It is here we get our first prompt towards the complexity of thought that built the work.

October 1935 takes its name from the first poem of the series Six Memorials by Ursula Bethell. Bethell is a New Zealand-British poet, active in her later years during the 1920s and 1930s. There is much scholarly debate about Bethell, and this includes her sexuality and whether it informed her decision to use a pen name,1 or if she truthfully wished anonymity in the eye of provincial publicity being a “painful affair”.2 This debate extends to, and is informed by, the nature of her relationship with her live-in companion Effie Pollen, who lived with Bethell for 30 years in various New Zealand addresses.

It is simple, yet remarkably complex. It takes several watches, each differently considered, and a few conversations with friends to unpack even a fraction of what is being presented. There is no floor sheet, only a small stack of waxy greige pages with the titular poem typed up. It is here we get our first prompt towards the complexity of thought that built the work.

October 1935 takes its name from the first poem of the series Six Memorials by Ursula Bethell. Bethell is a New Zealand-British poet, active in her later years during the 1920s and 1930s. There is much scholarly debate about Bethell, and this includes her sexuality and whether it informed her decision to use a pen name,1 or if she truthfully wished anonymity in the eye of provincial publicity being a “painful affair”.2 This debate extends to, and is informed by, the nature of her relationship with her live-in companion Effie Pollen, who lived with Bethell for 30 years in various New Zealand addresses.

Bethell’s debut collection of poetry was titled From a Garden in the Antipodes (1929), and was published under her pseudonym Evelyn Hayes. There are several objects of note that occur with this publication which feed into the “constellation of references”3 permeating Winter’s work. Looking at this point in time, the name ‘Evelyn’ was not socially gendered as it is now—the name was distinctly unisex, and not notably feminine until sometime after World War Two. The collection also debuted in London by publishers Segwick and Jackson, and was distinctly of an Australasian geography as opposed to a European locale. These distinct oppositional points between author and pseudonym, Empire and Colony, obfuscation and exposure, present an opportunity to occupy a range of textual positions otherwise not afforded by the burdens of reality. New Zealand poet Janet Charman put it quite plainly in the 1980s Spring issue of Women’s Studies Journal:

All of this history feeds into the publication of Six Memorials. Bethell never wrote under her own name, always credited as the author of From a Garden, and only used her own name in her sunset years. Pollen passed away in 1934, and this affected Bethell greatly: she wrote that this was “deeply shattering”, and hardly wrote past this point. Six Memorials was published for the first time in a collection of posthumous poetry in 1950, which she had been working on before her death in 1945. The correspondence between herself and publishers referred to them as her “saddest poems”. They are the first examples of Bethell’s work intentionally referencing her relationship with Pollen in the published sphere, and it is done after they had both passed.

There is an awful lot obscured and hidden here that Winter builds upon with this video. Presumably, the figure is reciting the poem that the show takes its name from—its muffled, broken voice engages with Bethell’s obscurity of queerness, and becomes a filmic interpretation of this poetic strategy. Poetry is rife with metaphor and roundabout descriptions, occasionally obfusticating as a writing approach. Tying this to queer language, and that of Bethell’s period, truths become hidden and made coded as a methodology for survival. If one spoke plainly, for instance, of love for another that one was not societally supposed to, you might be condemned to hard labour with Oscar Wilde. But actuating a push/pull linguistic approach of deliberate disguise might offer you a mechanism for self expression in a hyper-limiting society, and if you use a masc pen name and publish on the other side of the globe, the desired effects may be compounded.

The brief description of the exhibition listed on the RM website contains the phrase “enacts a private ritual of mourning”. This certainly has the energy of a form of grief, one of perhaps lamenting the existence of these survivalist linguistic barriers. There is also reference to Tiffany Page and their concept of vulnerable methodology. The quote used is in relation to the ethics of telling the stories of others: “as well as exposing the fragility of knowledge assembly, a vulnerable methodology might be closely positioned with questioning what is known, and what might come from an opening in not knowing.”4

In 1895, the year Bethell turned twenty one, Oscar Wilde was sentenced to two years with hard labour for homosexual practices. Understandably, even thirty four years later in New Zealand, Bethell sidesteps any hint of ‘daring’ as she details the ordinary intimacy of spouse with same-sex spouse.

All of this history feeds into the publication of Six Memorials. Bethell never wrote under her own name, always credited as the author of From a Garden, and only used her own name in her sunset years. Pollen passed away in 1934, and this affected Bethell greatly: she wrote that this was “deeply shattering”, and hardly wrote past this point. Six Memorials was published for the first time in a collection of posthumous poetry in 1950, which she had been working on before her death in 1945. The correspondence between herself and publishers referred to them as her “saddest poems”. They are the first examples of Bethell’s work intentionally referencing her relationship with Pollen in the published sphere, and it is done after they had both passed.

There is an awful lot obscured and hidden here that Winter builds upon with this video. Presumably, the figure is reciting the poem that the show takes its name from—its muffled, broken voice engages with Bethell’s obscurity of queerness, and becomes a filmic interpretation of this poetic strategy. Poetry is rife with metaphor and roundabout descriptions, occasionally obfusticating as a writing approach. Tying this to queer language, and that of Bethell’s period, truths become hidden and made coded as a methodology for survival. If one spoke plainly, for instance, of love for another that one was not societally supposed to, you might be condemned to hard labour with Oscar Wilde. But actuating a push/pull linguistic approach of deliberate disguise might offer you a mechanism for self expression in a hyper-limiting society, and if you use a masc pen name and publish on the other side of the globe, the desired effects may be compounded.

The brief description of the exhibition listed on the RM website contains the phrase “enacts a private ritual of mourning”. This certainly has the energy of a form of grief, one of perhaps lamenting the existence of these survivalist linguistic barriers. There is also reference to Tiffany Page and their concept of vulnerable methodology. The quote used is in relation to the ethics of telling the stories of others: “as well as exposing the fragility of knowledge assembly, a vulnerable methodology might be closely positioned with questioning what is known, and what might come from an opening in not knowing.”4

Bringing this back around to Bethell, we can see how his debate therefore can breach into the realm of trauma. Narrating the stories of others can become a form of violence, even when it is done so in a manner of appreciation. This brings us to the subject of ethics: Page suggests that we should engage with a vulnerability of not knowing as a form of investigative respect and what research and understanding may come from the acknowledgement of our not knowing.

Does all of this information on Bethell and her theorised queerness help us understand Winter’s work more, upgrade the level of pleasure of watching video work in a small concrete room nestled behind a car park? Are we any more connected to the thought and research scaffolding the work for having known? Or, are we able to understand and interpret the pulsing mouth’s nonlinguistic communication just fine, simultaneously acknowledging the absolute absurdity and limitations of language?

This is the nature of how we communicate: that language cannot effectively express the nuances of time, need, interpersonal relationships and socio-geographic barriers, and that attempting to do so can lead to assumptions, thereby inflicting trauma. The tension between the research and the expression of it has been captured in this video, and speaks to an overarching idea of how free we are to communicate to each other, or, whether our perceived freedom is in fact a breach upon another’s right to exist on their own terms. Circumnavigating conventional speech, Winter’s work here functions as a record of the complexity and capacity of conversation and understanding, of grief as an ethical approach, and all with an acute sense of self-awareness within the space.

1. Janet Charman, ‘My Ursula Bethell’, (1988) Women’s Studies Journal 14.2 pg 91-108. Accessed via NZEPC https://www.nzepc.auckland.ac.nz/misc/charman.asp

2. Peter Whiteford, ‘Ursula Bethel 1874 – 1945’, (2008): Kōtare : Special Issue - Essays in New Zealand Literary Biography Series Three: ‘The Early Poets’, Vol. 7 No. 3. Accessed via Victoria University OJS Archives https://ojs.victoria.ac.nz/kotare/article/view/707

3. Scourced from exhibition online listing https://rm.org.nz/

4. Tiffany Page, vulnerable writing as a feminist methodological practice. Fem Rev 115, 13–29 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41305-017-0028-0

Aliyah Winter, October 1935, 2023. 22 March – 15 April 2023 at RM, Tāmaki Makaurau.

All photos by Ardit Hoxha: Aliyah Winter, October 1935, 2023. Installation view at RM gallery. Courtesy of RM and the artist.

![]()

Does all of this information on Bethell and her theorised queerness help us understand Winter’s work more, upgrade the level of pleasure of watching video work in a small concrete room nestled behind a car park? Are we any more connected to the thought and research scaffolding the work for having known? Or, are we able to understand and interpret the pulsing mouth’s nonlinguistic communication just fine, simultaneously acknowledging the absolute absurdity and limitations of language?

This is the nature of how we communicate: that language cannot effectively express the nuances of time, need, interpersonal relationships and socio-geographic barriers, and that attempting to do so can lead to assumptions, thereby inflicting trauma. The tension between the research and the expression of it has been captured in this video, and speaks to an overarching idea of how free we are to communicate to each other, or, whether our perceived freedom is in fact a breach upon another’s right to exist on their own terms. Circumnavigating conventional speech, Winter’s work here functions as a record of the complexity and capacity of conversation and understanding, of grief as an ethical approach, and all with an acute sense of self-awareness within the space.

1. Janet Charman, ‘My Ursula Bethell’, (1988) Women’s Studies Journal 14.2 pg 91-108. Accessed via NZEPC https://www.nzepc.auckland.ac.nz/misc/charman.asp

2. Peter Whiteford, ‘Ursula Bethel 1874 – 1945’, (2008): Kōtare : Special Issue - Essays in New Zealand Literary Biography Series Three: ‘The Early Poets’, Vol. 7 No. 3. Accessed via Victoria University OJS Archives https://ojs.victoria.ac.nz/kotare/article/view/707

3. Scourced from exhibition online listing https://rm.org.nz/

4. Tiffany Page, vulnerable writing as a feminist methodological practice. Fem Rev 115, 13–29 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41305-017-0028-0

Aliyah Winter, October 1935, 2023. 22 March – 15 April 2023 at RM, Tāmaki Makaurau.

All photos by Ardit Hoxha: Aliyah Winter, October 1935, 2023. Installation view at RM gallery. Courtesy of RM and the artist.

ISSN 2744-7952

Thank you for reading ︎

Vernacular logo designed by Yujin Shin

vernacular.criticism ︎