Hair/Here

Misaeng by Min-Young Her

Misaeng | Min-Young Her | play_station, Pōneke

9.12.22 | written by Vanessa Crofskey

Misaeng by Min-Young Her is a deceptively simple exhibition. Held at play_station space in Te Whanganui-a-Tara, the show explores how human beings relate to each other across lifetimes and places, through the artist’s tracing of her personal lineage. For many migrants, the uncovering of ancestry also creates a bespoke cartography of locations, and Misaeng draws physical threads that connect South Korea, Her’s place of origin, to Aotearoa, where the artist and her family currently reside.

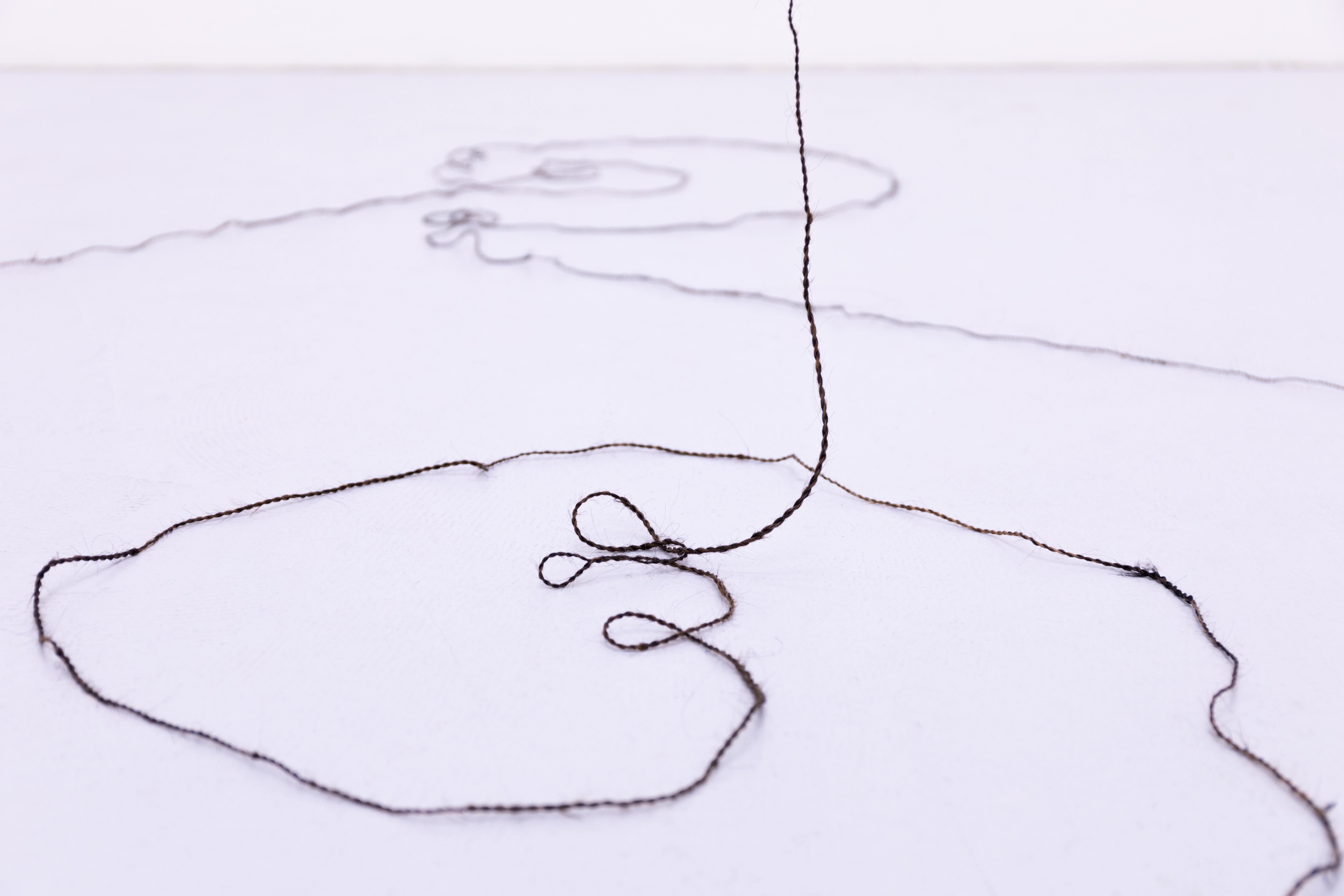

In Misaeng, these connective threads, across timelines and oceans, are presented primarily through hair. Specifically, it is the artist’s own hair, shaved from her scalp and then repurposed: a neat 155 grams of exhibition material that lengthens into sixty-to-one-hundred metres of rope, which takes up nearly the entirety of play_station’s roughly ten-by-four metre gallery. Tens of thousands of individual strands are bound into a delicate cord that falls from the ceiling in loops and circles, that coils into spirals across the bare floor. The ends are untwisted, left like a promise that they could later be rejoined.

In her artistic practice, Her is interested in human relationships, in how fluid the connections between the self and other selves can be. These interests take up both materially tactile and often performative bents that circumvent the rigid social expectations of the white cube. As mentioned to host Rachel Liao in an interview on the B-Side Podcast, “when I was younger I was always drawn to performance art, other means of sharing or engaging with creative experiences” which grew into what Her is interested in today: “a very explicit or implicit connection between bodies, connections between the audience and myself as the artist, or the works and the audience.”

The implication of bodies, past and present, takes up centre space for the audience in Misaeng, Her’s latest solo. The relationships that are present are contained within the material; in the long and looping rope of hair which “looks almost so delicate that if you touched it it would all fall apart” and the way that the material allures you for a touch, suggesting your own entanglement with its affairs.

In Misaeng, these connective threads, across timelines and oceans, are presented primarily through hair. Specifically, it is the artist’s own hair, shaved from her scalp and then repurposed: a neat 155 grams of exhibition material that lengthens into sixty-to-one-hundred metres of rope, which takes up nearly the entirety of play_station’s roughly ten-by-four metre gallery. Tens of thousands of individual strands are bound into a delicate cord that falls from the ceiling in loops and circles, that coils into spirals across the bare floor. The ends are untwisted, left like a promise that they could later be rejoined.

In her artistic practice, Her is interested in human relationships, in how fluid the connections between the self and other selves can be. These interests take up both materially tactile and often performative bents that circumvent the rigid social expectations of the white cube. As mentioned to host Rachel Liao in an interview on the B-Side Podcast, “when I was younger I was always drawn to performance art, other means of sharing or engaging with creative experiences” which grew into what Her is interested in today: “a very explicit or implicit connection between bodies, connections between the audience and myself as the artist, or the works and the audience.”

The implication of bodies, past and present, takes up centre space for the audience in Misaeng, Her’s latest solo. The relationships that are present are contained within the material; in the long and looping rope of hair which “looks almost so delicate that if you touched it it would all fall apart” and the way that the material allures you for a touch, suggesting your own entanglement with its affairs.

Min-Young Her, Misaeng, 2022. Detail. The artist’s hair.

Through hair, you can find out a person’s biologically woven source code. This phenomenon is called ‘maternal inheritance,’ a byproduct of human design that reveals a person’s matriarchal heritage through the mitochondrial DNA data found within a single strand. As opposed to a broad attempt at studying human relationships, the body-to-body proximity that is examined in Misaeng is closely familial: by using her own hair, Her’s relationship to her mother, her mother’s mothers and their mothers before them are intertwined in the same locality, open for us to postulate upon, and to imagine the inheritances of our own.

The title of the exhibition is taken from a phrase that the artist’s mother used to tell her, that ‘dying doesn’t mean your life is finished.’ What does this mean exactly? Perhaps that after death, a human might continue to live on through the scattered cells of their body, dispersed into soil and air (“For dust you are, and to dust you shall return”).1 That your selfhood might exist within others, their synaptic jolts of memories, dreams and passing sensations. That your body might inherit the genetic composition of its ancestors, and you too may pass on this inheritance—might continue the rope.

The fibre within this exhibition, the thin strands of hair, is ever-present, primarily dark in colour and straight in temperament, with subtle gradients where the colour shifts into moments of soft brown and then blonde. I am pulled toward the blonde, its soft recognition of fluctuations within one’s appearance—perhaps something of Her’s that is not present in the experience of her female forebears. I too have had a blonde phase. The sensory subject matter allows for personal associations and cultural histories to permeate.

Going bleach blonde, imo, is a contemporary Asian woman’s cultural rite. For many East Asian cultures, there exists a historical apprehension (and at times, open hostility) to body modification that is prevalent in the mindsets of previous generations. In conventional Confucianism, “care-of-self and preserving the body were seen as important expressions of filial piety.”2 There’s a common idea held across many East Asian cultures that your body doesn’t just belong to you but also to your parents—your self as their offspring acts as a reflection of their own selves, hence there is less condoned ability to do whatever you like to your appearance, given that it belongs not only to you but your entire family (see: Mulan).

Much has changed since the turn of the century, with cosmetic body practices now common across younger generations from East Asian cultures. The intentional changing of one’s body, through piercings, tattoos and the like can be seen as a cultural rite that rejects notions of tradition, a protestive reclamation of one’s self-made heritage and self-agency. Hence, the blonde phase.

For Her, who daylights as a tattoo artist, the decision to shave her head for the show was a reconnection to more traditional and spiritual aspects of her heritage, including the transformation that Buddhist monks go through by shaving their own heads as an act of religious devotion. A life and death ritual cited in the exhibition text that appears pre-Buddhism is ‘sitkimgut’, a rite conducted by mudang (Korean shamans) for “transforming or cleansing someone’s death or negative energies”.3 This rite is performed predominantly by women and although it varies, it typically includes a dance in a circular formation following only one direction.

While the show draws on Korean Buddhist and Shamanistic practices, it’s not aiming to replicate or make commentary on them in any ‘pure’ way. Rather these specific cultural histories act as a loose portal of references for a personal and artistic inquiry into life and heritage. I keep returning to the act of Her shaving her head for the show as the private accompanying performance to the exhibition. While it’s not the same reason as a monk might shave their head, there are cross-overs: a small death required to renew one’s self. The trail of influence left by the ‘sitkimgut’ is not obvious materially. However, one can sense its residue in the hours of repetitive action it would take for Her to thread her own hair together through blistered fingers, the meditative act of rolling cord in one direction where the bottle blonde is joined with the thick, dark hair of its origins.

Life, too, appears to follow only one direction: from new to old, birth to death. But like the timelines that appear in Misaeng, it loops and circles as much as genealogies coiled within mitochondrial DNA. To me, the composition of hair within this show (which funnily enough, resists decomposition) has no linear direction. Rather the direction of the rope is left open-ended, left for the audience to decide which is the beginning and the end, or neither and both—with those end strands left untethered. It’s a show made mostly of Her’s hair, that speaks to the histories and migration of her female ancestors, and the cultural and spiritual contexts of time periods. Flipped the other way around, it could be seen as a show where Her acts as a vessel for these maternal forebears to speak their beings into a physical setting.

The title of the exhibition is taken from a phrase that the artist’s mother used to tell her, that ‘dying doesn’t mean your life is finished.’ What does this mean exactly? Perhaps that after death, a human might continue to live on through the scattered cells of their body, dispersed into soil and air (“For dust you are, and to dust you shall return”).1 That your selfhood might exist within others, their synaptic jolts of memories, dreams and passing sensations. That your body might inherit the genetic composition of its ancestors, and you too may pass on this inheritance—might continue the rope.

The fibre within this exhibition, the thin strands of hair, is ever-present, primarily dark in colour and straight in temperament, with subtle gradients where the colour shifts into moments of soft brown and then blonde. I am pulled toward the blonde, its soft recognition of fluctuations within one’s appearance—perhaps something of Her’s that is not present in the experience of her female forebears. I too have had a blonde phase. The sensory subject matter allows for personal associations and cultural histories to permeate.

Going bleach blonde, imo, is a contemporary Asian woman’s cultural rite. For many East Asian cultures, there exists a historical apprehension (and at times, open hostility) to body modification that is prevalent in the mindsets of previous generations. In conventional Confucianism, “care-of-self and preserving the body were seen as important expressions of filial piety.”2 There’s a common idea held across many East Asian cultures that your body doesn’t just belong to you but also to your parents—your self as their offspring acts as a reflection of their own selves, hence there is less condoned ability to do whatever you like to your appearance, given that it belongs not only to you but your entire family (see: Mulan).

Much has changed since the turn of the century, with cosmetic body practices now common across younger generations from East Asian cultures. The intentional changing of one’s body, through piercings, tattoos and the like can be seen as a cultural rite that rejects notions of tradition, a protestive reclamation of one’s self-made heritage and self-agency. Hence, the blonde phase.

For Her, who daylights as a tattoo artist, the decision to shave her head for the show was a reconnection to more traditional and spiritual aspects of her heritage, including the transformation that Buddhist monks go through by shaving their own heads as an act of religious devotion. A life and death ritual cited in the exhibition text that appears pre-Buddhism is ‘sitkimgut’, a rite conducted by mudang (Korean shamans) for “transforming or cleansing someone’s death or negative energies”.3 This rite is performed predominantly by women and although it varies, it typically includes a dance in a circular formation following only one direction.

While the show draws on Korean Buddhist and Shamanistic practices, it’s not aiming to replicate or make commentary on them in any ‘pure’ way. Rather these specific cultural histories act as a loose portal of references for a personal and artistic inquiry into life and heritage. I keep returning to the act of Her shaving her head for the show as the private accompanying performance to the exhibition. While it’s not the same reason as a monk might shave their head, there are cross-overs: a small death required to renew one’s self. The trail of influence left by the ‘sitkimgut’ is not obvious materially. However, one can sense its residue in the hours of repetitive action it would take for Her to thread her own hair together through blistered fingers, the meditative act of rolling cord in one direction where the bottle blonde is joined with the thick, dark hair of its origins.

Life, too, appears to follow only one direction: from new to old, birth to death. But like the timelines that appear in Misaeng, it loops and circles as much as genealogies coiled within mitochondrial DNA. To me, the composition of hair within this show (which funnily enough, resists decomposition) has no linear direction. Rather the direction of the rope is left open-ended, left for the audience to decide which is the beginning and the end, or neither and both—with those end strands left untethered. It’s a show made mostly of Her’s hair, that speaks to the histories and migration of her female ancestors, and the cultural and spiritual contexts of time periods. Flipped the other way around, it could be seen as a show where Her acts as a vessel for these maternal forebears to speak their beings into a physical setting.

Min-Young Her, Misaeng, 2022. Installation view. The artist’s hair.

Hair can be tough subject material to tackle, replete with so many political, personal and sensory histories. It risks being overburdened by associations (gender, queerness, witchcraft, Mona Hatoum) or by the tactility of its material (kind of gross once removed from the scalp). But these stronger associations feel less relevant being that here it is used primarily as the conduit for a wider discussion on inheritance.

Featured in the exhibition text are quotes from In Memory of Memory by Maria Stepanova, who writes about the concept of postmemory: “the ceaseless fascination with one’s family’s past…”, an internal language that references the concept of “transgenerational transmission of traumatic knowledge and experience”.4 Intergenerational experiences are innate for immigrants and their offspring, a transmission that can omit itself from the pages of documented history, but exists in the memories deposited deep under the skin, within the very biology of a human body.

There’s a tension between the contemporary and the traditional that has been captured in these thin strands that speak to an overarching idea of beginning anew, of life and death twirling like a double helix. Her’s hair and its transformations within the exhibition functions as a record of self-becoming, or more complexly, of multiple selves, collectively binding.

Min-Young Her, Misaeng, 2022. 01 September – 24 September 2022 at play_station, Pōneke.

Photos: By Sage Rossie, courtesy of play_station and the artist.

Article image: Min-Young Her, Misaeng, 2022. Detail. The artist’s hair.

1. So says God, according to Genesis 3:19.

2. David Henley & Nathan Porath (2021) ‘Body Modification in East Asia: History and Debates,’ Asian Studies Review. 45:2, pp.198–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/10357823.2020.1849026

3. Sourced from exhibition text. http://playstationartistrun.space/misaeng-minyoung-her

4. Maria Stepanova (2021) In Memory of Memory. Translated by Sasha Dugdale. Book*hug Press: Toronto.

Featured in the exhibition text are quotes from In Memory of Memory by Maria Stepanova, who writes about the concept of postmemory: “the ceaseless fascination with one’s family’s past…”, an internal language that references the concept of “transgenerational transmission of traumatic knowledge and experience”.4 Intergenerational experiences are innate for immigrants and their offspring, a transmission that can omit itself from the pages of documented history, but exists in the memories deposited deep under the skin, within the very biology of a human body.

There’s a tension between the contemporary and the traditional that has been captured in these thin strands that speak to an overarching idea of beginning anew, of life and death twirling like a double helix. Her’s hair and its transformations within the exhibition functions as a record of self-becoming, or more complexly, of multiple selves, collectively binding.

Min-Young Her, Misaeng, 2022. 01 September – 24 September 2022 at play_station, Pōneke.

Photos: By Sage Rossie, courtesy of play_station and the artist.

Article image: Min-Young Her, Misaeng, 2022. Detail. The artist’s hair.

1. So says God, according to Genesis 3:19.

2. David Henley & Nathan Porath (2021) ‘Body Modification in East Asia: History and Debates,’ Asian Studies Review. 45:2, pp.198–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/10357823.2020.1849026

3. Sourced from exhibition text. http://playstationartistrun.space/misaeng-minyoung-her

4. Maria Stepanova (2021) In Memory of Memory. Translated by Sasha Dugdale. Book*hug Press: Toronto.

ISSN 2744-7952

Thank you for reading ︎

Vernacular logo designed by Yujin Shin

vernacular.criticism ︎