Homefire

Exhibition by Sorawit Songsataya

Homefire | Sorawit Songsataya | Paludal, Ōtautahi

31.03.22 | written by Jane Wallace

The chapter “Open Lands” in Édouard Glissant’s Poetic Intention opens with a world that crackles. He describes “places where vocation, presence, the warmth of the entire world surface: Ibadan is among these. A city without monuments, but where perfection crackles in the presence of the world.”1 This heat that Glissant perceives is not about temperature, but rather the incandescence of communal energy. Sorawit Songsataya’s exhibition homefire, at the newly reopened Paludal in Ōtautahi is similarly evocative of a shared presence in the world. Attending to the language of a domestic fire, homefire considers the hearth as an enduring site of collectivity.

In the centre of the gallery is a sculptural stack of logs hewn from Ōamaru limestone and beeswax, titled Cabined (2021). Arranged cross-hatch, the work is a fireplace readied but unlit: the suggested work of sawing, gathering, and stacking poised before ignition. In Cabined, though, the typical preparation of a fire is substituted by Songsataya’s process of carving, melting and casting their materials. This parallel makes the elements of collaboration, survival and care visible in their work; and also, the energy and nutrients involved in growing a tree, the effort of the beehive in producing beeswax, or minerals calcifying into porous stone.

In the centre of the gallery is a sculptural stack of logs hewn from Ōamaru limestone and beeswax, titled Cabined (2021). Arranged cross-hatch, the work is a fireplace readied but unlit: the suggested work of sawing, gathering, and stacking poised before ignition. In Cabined, though, the typical preparation of a fire is substituted by Songsataya’s process of carving, melting and casting their materials. This parallel makes the elements of collaboration, survival and care visible in their work; and also, the energy and nutrients involved in growing a tree, the effort of the beehive in producing beeswax, or minerals calcifying into porous stone.

Homefire, Sorawit Songsataya, 2022. Installed at Paludal.

Homefire, Sorawit Songsataya, 2022. Installed at Paludal. Simon Palenski, in the exhibition text for homefire, notes the emotional response of archaeologists uncovering a fireplace or hearth on a dig. He observes that the thrill is not merely in unearthing the fragments of pottery or tile, but also in the revelation of a site where some ancient gathering would have occurred.2 There is an emotional chord in crouching in the same place where others, unknown, thousands of years ago, would have — an affect of pulling past and present a little closer together through mimicry. Cabined replicates this emotive experience twofold. On opening night, we huddle around the work. As such, the motion of crouching around an arrangement of fire can be the comfort itself, and this communal energy is what Songsataya’s work is so adept at generating.

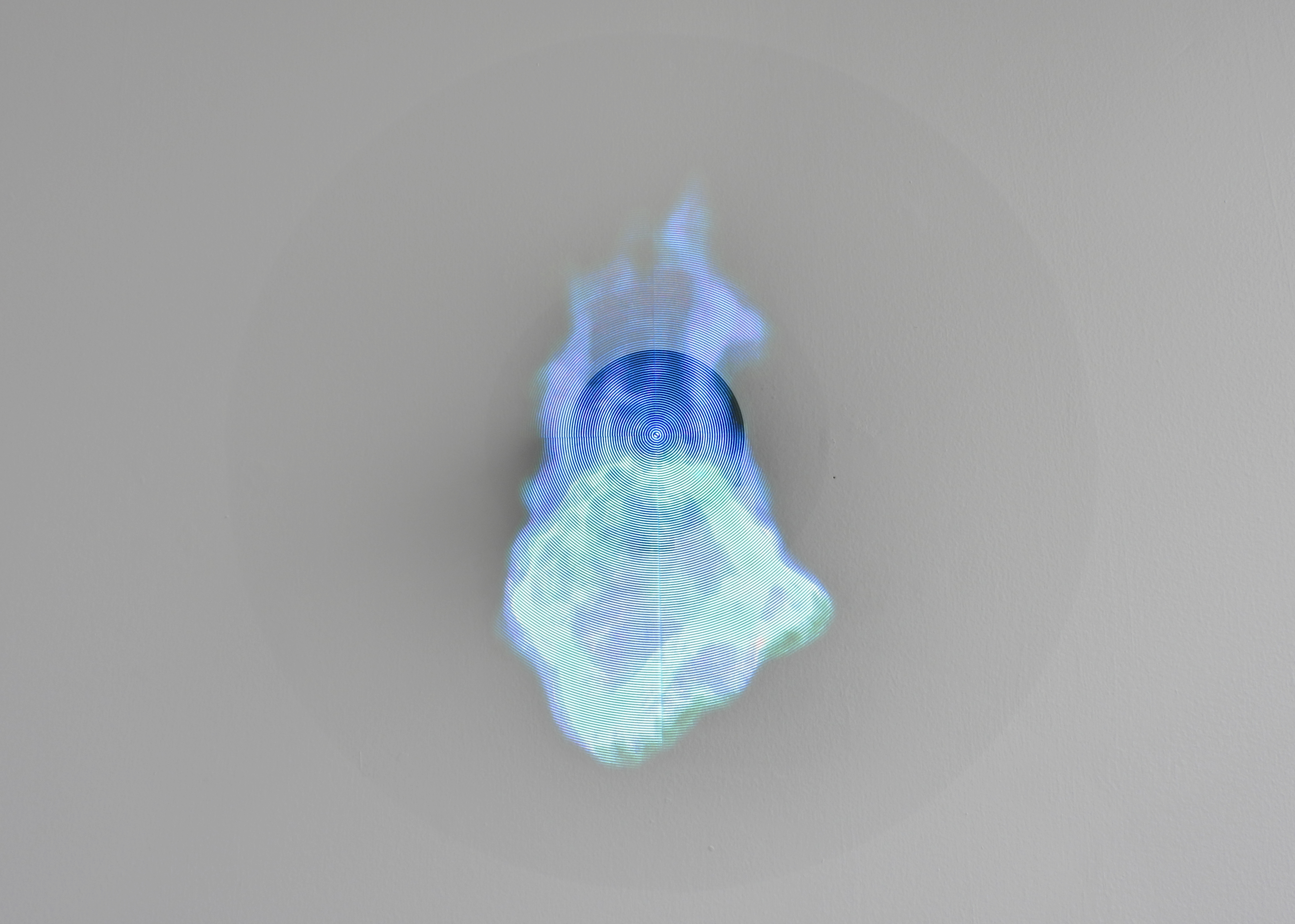

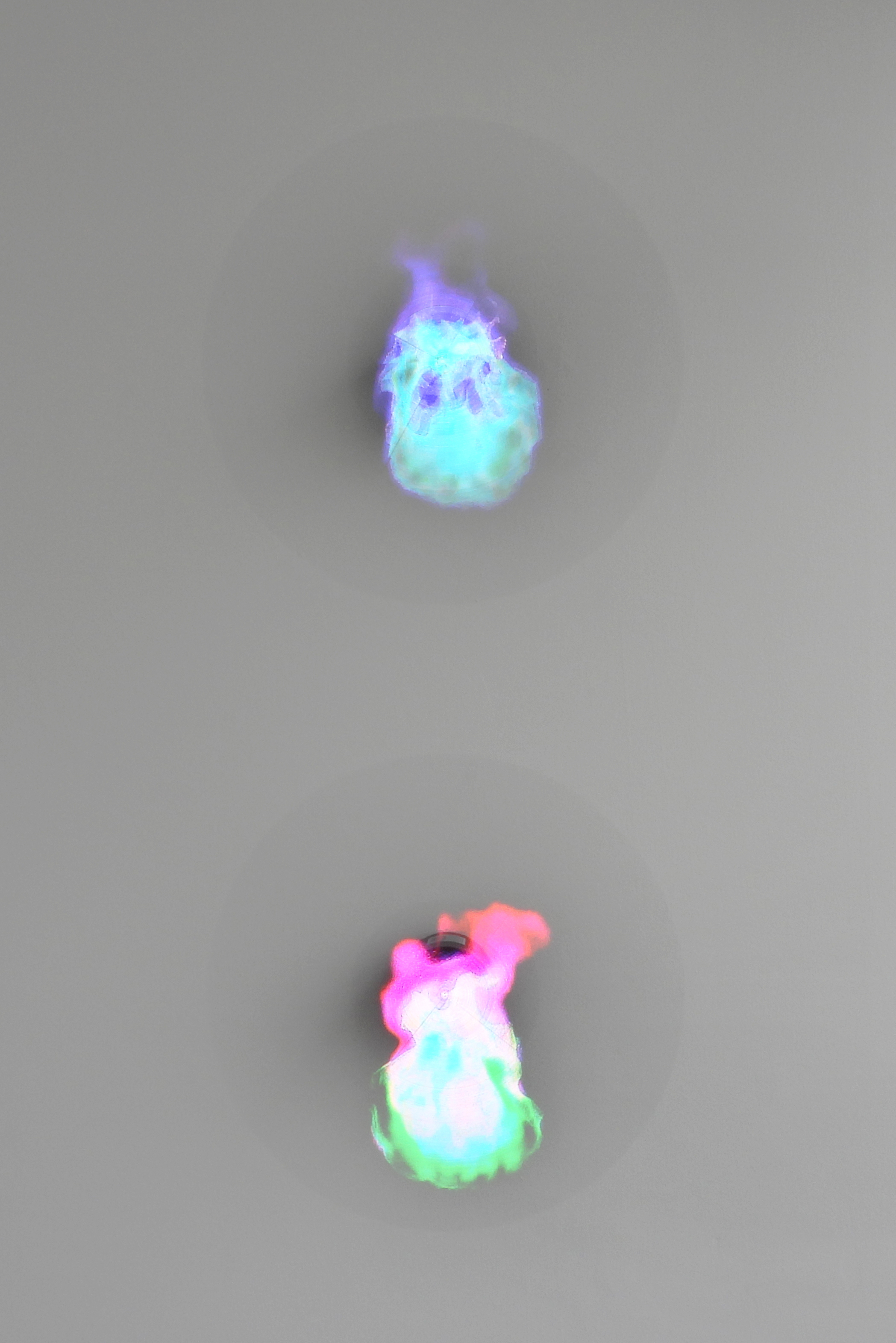

On the far wall, Light years (2022), a digital diptych has been installed, constituting a counterpart for Cabined. Light years comprises two 3D holographic fans, whirring with the two-channel animation of a blue and purple inferno. The labour involved in starting a fire is mirrored here; to create an eight minute hologram requires hours spent developing strings of code and different static frames that will merge to form a continually dancing tongue of flame. I research the process of computer-based animation and learn that the image file that contains these iterations of movement is called a sprite sheet. The animated dimension of Songsataya’s work is playful, a mode of world-building that prioritises imagination. A sprite in the gallery: a magical creature that refuses the linearity of time, or the logics of reality that it exists within.

On the far wall, Light years (2022), a digital diptych has been installed, constituting a counterpart for Cabined. Light years comprises two 3D holographic fans, whirring with the two-channel animation of a blue and purple inferno. The labour involved in starting a fire is mirrored here; to create an eight minute hologram requires hours spent developing strings of code and different static frames that will merge to form a continually dancing tongue of flame. I research the process of computer-based animation and learn that the image file that contains these iterations of movement is called a sprite sheet. The animated dimension of Songsataya’s work is playful, a mode of world-building that prioritises imagination. A sprite in the gallery: a magical creature that refuses the linearity of time, or the logics of reality that it exists within.

Light years, Sorawit Songsataya, 2021. Two-channel digital animation displayed on holographic fans.

Light years, Sorawit Songsataya, 2021. Two-channel digital animation displayed on holographic fans.There is a tension between the primeval materiality of Cabined and the digital production of Light years, as if this is a fire taking place across eons. The Ōamaru stone used in Cabined is a mineral that can be dated to somewhere between five and 23 million years ago, and the earliest human usage of beeswax is thought to be during Neolithic times. Conversely, computer rendered imagery and its applications are advancing every day, and the potential for their continued evolution is seemingly infinite. In this juxtaposition, this is a fire that can span the ether of natural and human histories. As Robyn Maree Pickens has written in their essay on The Interior (Auckland Art Gallery, 2019), an ongoing theme of Songsataya’s practice is how to move past the dualism of nature and culture. Pickens writes, “for certainly, an inability to see ourselves as part of the rest of nature contributes to distancing, alienation and the view of ‘nature’ as a resource and therefore expendable.”3 Subsequently, the building of a fire elicits questions of deforestation and pollution, yet Songsataya has divorced fuel and flame. The wood will not run out; the embers will not be extinguished. The domestic fire acts as a ubiquitous symbol of synchronised systems across human and non-human, and this consideration of the natural world is vital to Songsataya’s practice.

The word heart lives inside hearth, a love encased by heat and kindling. I haven’t yet mentioned the soft scent of beeswax that rises in the exhibition, a sweet residue of honeybees working together. Homefire expounds a way of thinking that is dependent on relationships between beings, oscillating between the one and the many, and across the crackling plane of the world. As David Teh expresses though, the recurring dimension of distance in contemporary Thai art is “an index of loss, of longing for the people and comforts of home.”4 In these terms, the specific cultural logic of distance is visceral in homefire, as Sonsataya’s experience of growing further away from Thailand and their own Thai-ness is reflected in their exploration of how to make a spatio-temporal return. And so, in the meantime, they tend to an everlasting fire, here, but also light years away.

Homefire, Sorawit Songsataya, 2022. March 10 – April 3 2022, Paludal, Ōtautahi.

Images courtesy of the artist and Paludal.

![]()

Article image: Light years, Sorawit Songsataya, 2021. Two-channel digital animation displayed on holographic fans. Detail.

1. Édouard Glissant, “Open Lands,” in Poetic Intention, translated by Nathanaël. Calicoon, New York: Nightboat Books, 2010. P. 146.

2. Simon Palenski, “The Hearth and the Volcano,” exhibition text for Homefire, Paludal, Christchurch, 2022.

3. Robyn Maree Pickens, “Life In The Interior: Sorawit Songsataya,” Auckland Art Gallery brochure, 2019.

4. David Teh, “Nirat: Distance, Itinerancy and Homesickness as a Spatial Logic,” in Thai Art: Currencies of the Contemporary. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2017. P. 91.

Further reading, homefire, review by Orissa Keane on Artbeat.

The word heart lives inside hearth, a love encased by heat and kindling. I haven’t yet mentioned the soft scent of beeswax that rises in the exhibition, a sweet residue of honeybees working together. Homefire expounds a way of thinking that is dependent on relationships between beings, oscillating between the one and the many, and across the crackling plane of the world. As David Teh expresses though, the recurring dimension of distance in contemporary Thai art is “an index of loss, of longing for the people and comforts of home.”4 In these terms, the specific cultural logic of distance is visceral in homefire, as Sonsataya’s experience of growing further away from Thailand and their own Thai-ness is reflected in their exploration of how to make a spatio-temporal return. And so, in the meantime, they tend to an everlasting fire, here, but also light years away.

Homefire, Sorawit Songsataya, 2022. March 10 – April 3 2022, Paludal, Ōtautahi.

Images courtesy of the artist and Paludal.

Article image: Light years, Sorawit Songsataya, 2021. Two-channel digital animation displayed on holographic fans. Detail.

1. Édouard Glissant, “Open Lands,” in Poetic Intention, translated by Nathanaël. Calicoon, New York: Nightboat Books, 2010. P. 146.

2. Simon Palenski, “The Hearth and the Volcano,” exhibition text for Homefire, Paludal, Christchurch, 2022.

3. Robyn Maree Pickens, “Life In The Interior: Sorawit Songsataya,” Auckland Art Gallery brochure, 2019.

4. David Teh, “Nirat: Distance, Itinerancy and Homesickness as a Spatial Logic,” in Thai Art: Currencies of the Contemporary. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2017. P. 91.

Further reading, homefire, review by Orissa Keane on Artbeat.

ISSN 2744-7952

Thank you for reading ︎

Vernacular logo designed by Yujin Shin

vernacular.criticism ︎