Hate to rain on your parade

Exhibition by Hannah Ireland

Hate to rain on your parade | Hannah Ireland | Sanc Gallery, Tāmaki Makaurau

15.11.21 | written by Theo Macdonald

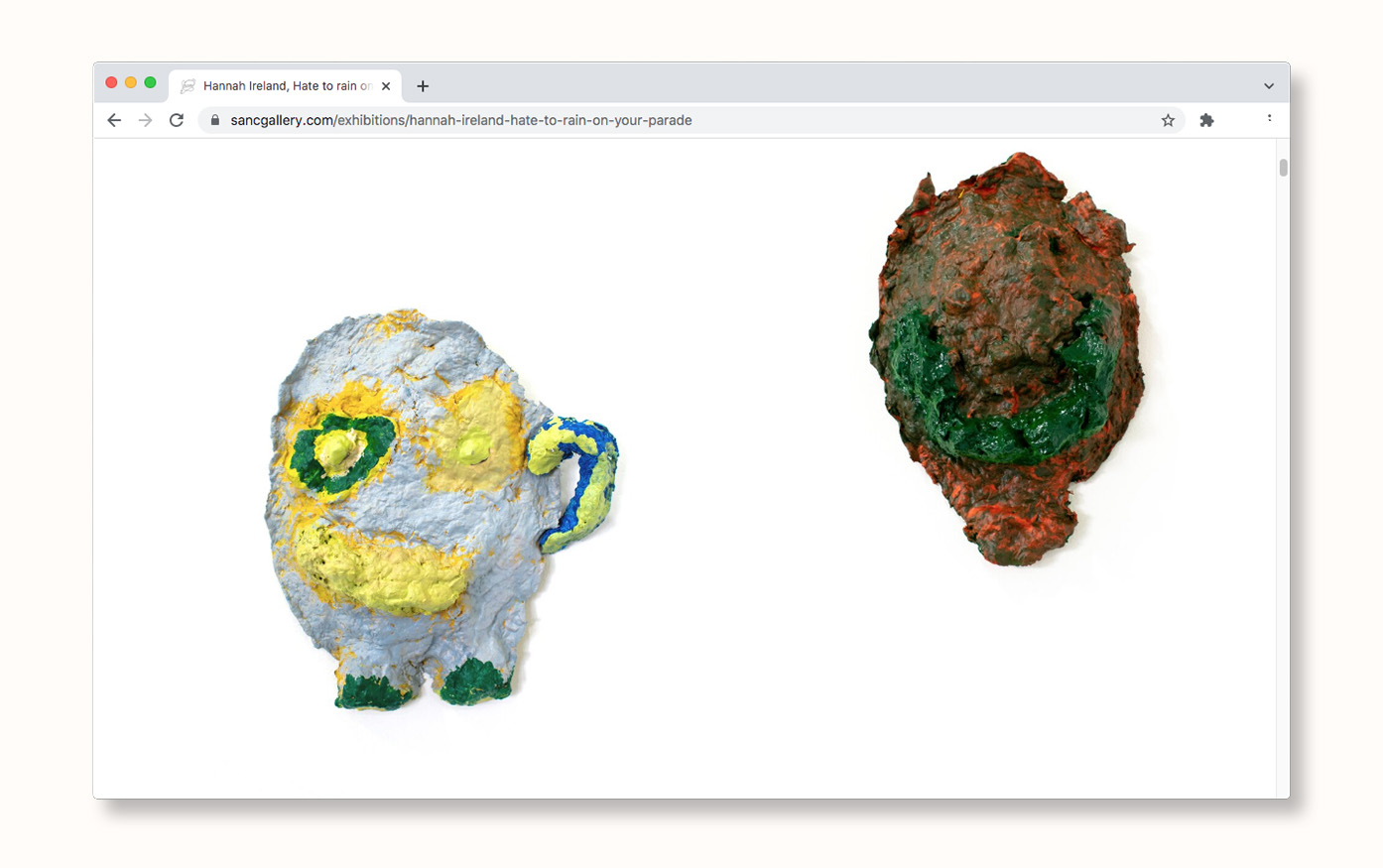

Hannah Ireland’s painting exhibition Hate to rain on your parade existed offline at Sanc Gallery on upper Queen Street, in central Tāmaki Makaurau. I’ve never visited the space, and for the time being Sanc is solely a website1. Since early 2020, institutions have shifted to online exhibition-making with mixed success. Hate to rain on your parade has been adapted with intention. The online leg is more than just wide installation shots interrupted by the occasional close-up of a puckered canvas.

The first works in the vertical scroll are two bulbous masks sculpted from paper pulp and fixed in acrylic. The left hand mask is the colour of a school play cloud, with one lemon drop ear curled like a teapot. The one on the right is a sticky scab. Offset beside each other, they are scaled to fill the screen. A digital scalpel has removed the wall behind the masks, allowing them to hover against the white #ffffff backdrop of sancgallery.com. The thickness of each mask is a reminder of the beveled buttons of Web 2.0. Photoshop conversations with Annie Leibovitz, David Hockney remarks, “...isn’t it nice that we are painting again?”2

The work is divided into three sets: paper-pulp masks, 700mm x 800mm watercolours on stretched canvas, and smaller flat works grouped in a salon hang. Some of the latter are framed, others are on handmade paper. Scrolling down, these appear in a mix of install shots and full-frame flushes, some of which are trickily composed to mimic the install formation.

The first works in the vertical scroll are two bulbous masks sculpted from paper pulp and fixed in acrylic. The left hand mask is the colour of a school play cloud, with one lemon drop ear curled like a teapot. The one on the right is a sticky scab. Offset beside each other, they are scaled to fill the screen. A digital scalpel has removed the wall behind the masks, allowing them to hover against the white #ffffff backdrop of sancgallery.com. The thickness of each mask is a reminder of the beveled buttons of Web 2.0. Photoshop conversations with Annie Leibovitz, David Hockney remarks, “...isn’t it nice that we are painting again?”2

The work is divided into three sets: paper-pulp masks, 700mm x 800mm watercolours on stretched canvas, and smaller flat works grouped in a salon hang. Some of the latter are framed, others are on handmade paper. Scrolling down, these appear in a mix of install shots and full-frame flushes, some of which are trickily composed to mimic the install formation.

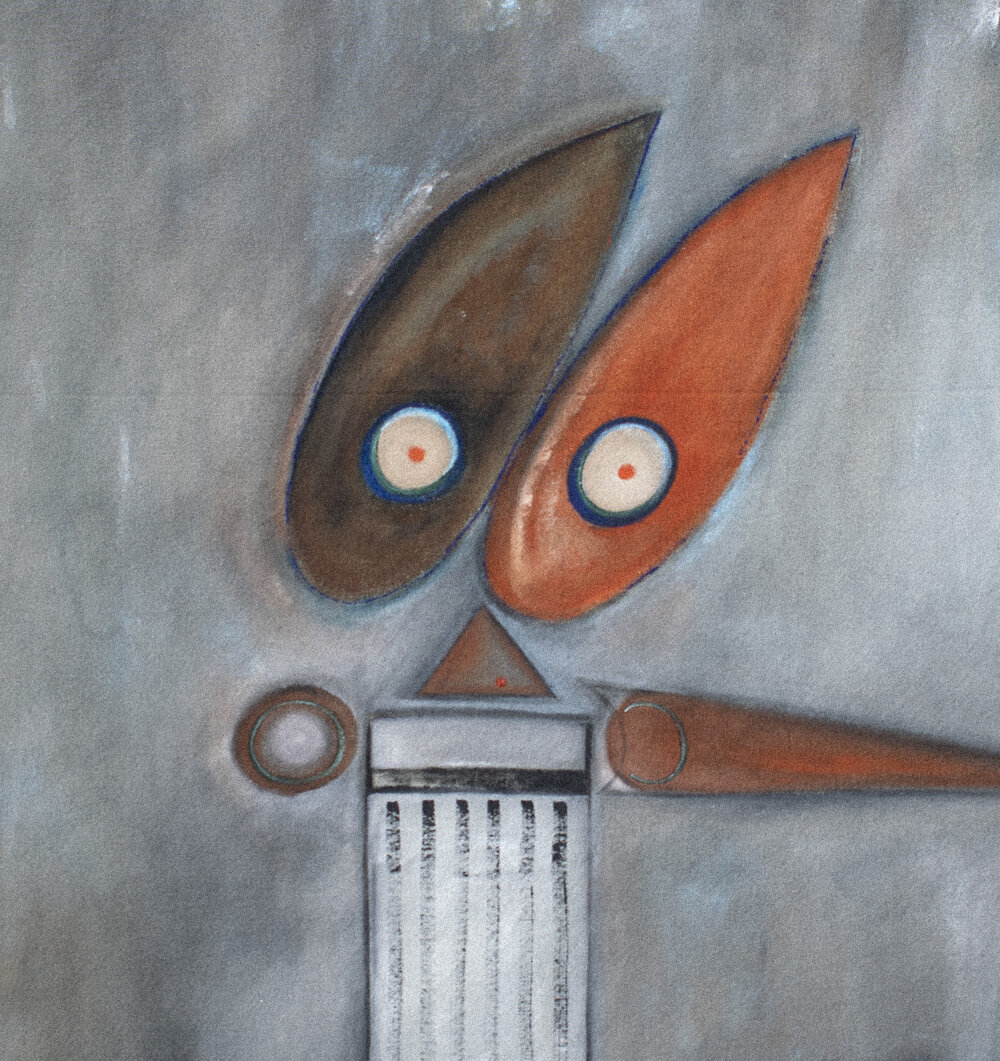

Directly behind us (2021)

Directly behind us (2021)Watercolour on streched canvas

700 x 750mm

The relationship between these two exhibitions—the online and the offline—is precarious, like screenplays published in book form for which the screenwriter retroactively annotates camera directions. The linear sequence of the online scroll marks a difference. The closest equivalent in real space would be a guided tour. It takes away the game of discovering the exhibition, but heightens the play within the work.

According to colour field painter Barnett Newman, “The self, terrible and constant, is for me the subject matter of painting.”3 Hannah Ireland’s paintings are all faces, all selves. They are not all heads. Most crop out the cranial parabola, the neck, the ears. And they turn from geometric abstractions into faces through the simplest addition: two circles, a triangle, and a squiggly line. Some stare. Some grimace. A few smile. Several cry. Ireland also really likes teeth.

My thoughts keep coming back to the mid-century cartoonist Saul Steinberg, whose practice incorporated assemblages and masks atop a foundation of drawing. Within Steinberg’s work, like Ireland’s, the contour line functions like a divining rod. Steinberg stains the page with a fingerprint and transforms it into a face with three abrupt lines. He innovates, plays games. His masks are upside-down grocery bags. He draws two circles for glasses, one line for a nose, a moustache scribble. Steinberg’s work is a partner to the typographic emoticon. Reaction as cliché. Through grin and grimace, Ireland sustains this subject of performed emotion.

Emojis. Why is it that we can emotionally invest in a reduced form, such as a cartoon, as much as a photograph? In Understanding Comics, theory guru Scott McCloud claims that when we simplify an object’s representative form we amplify the potency of the features retained. The smiley-face becomes a shell for us to inhabit, a mask. “When you look at a photo [...] you see it as the face of another, but when you enter the world of the cartoon you see yourself.”4

The pathos of Hannah Ireland’s paintings lives through their inhabitability, as does the humour. The titles of Ireland’s works are funny: Random bursts of laughter are my favourite, That’s enough silly business, and Take your dirty laundry and throw it over the fence. These phrases suggest theatrical play, social play, and childhood play as a context for learning. This amiability is extended by the crowd forming when Ireland’s faces are installed together.

According to colour field painter Barnett Newman, “The self, terrible and constant, is for me the subject matter of painting.”3 Hannah Ireland’s paintings are all faces, all selves. They are not all heads. Most crop out the cranial parabola, the neck, the ears. And they turn from geometric abstractions into faces through the simplest addition: two circles, a triangle, and a squiggly line. Some stare. Some grimace. A few smile. Several cry. Ireland also really likes teeth.

My thoughts keep coming back to the mid-century cartoonist Saul Steinberg, whose practice incorporated assemblages and masks atop a foundation of drawing. Within Steinberg’s work, like Ireland’s, the contour line functions like a divining rod. Steinberg stains the page with a fingerprint and transforms it into a face with three abrupt lines. He innovates, plays games. His masks are upside-down grocery bags. He draws two circles for glasses, one line for a nose, a moustache scribble. Steinberg’s work is a partner to the typographic emoticon. Reaction as cliché. Through grin and grimace, Ireland sustains this subject of performed emotion.

Emojis. Why is it that we can emotionally invest in a reduced form, such as a cartoon, as much as a photograph? In Understanding Comics, theory guru Scott McCloud claims that when we simplify an object’s representative form we amplify the potency of the features retained. The smiley-face becomes a shell for us to inhabit, a mask. “When you look at a photo [...] you see it as the face of another, but when you enter the world of the cartoon you see yourself.”4

The pathos of Hannah Ireland’s paintings lives through their inhabitability, as does the humour. The titles of Ireland’s works are funny: Random bursts of laughter are my favourite, That’s enough silly business, and Take your dirty laundry and throw it over the fence. These phrases suggest theatrical play, social play, and childhood play as a context for learning. This amiability is extended by the crowd forming when Ireland’s faces are installed together.

Hate to rain on your parade, installed at Sanc Gallery, Tāmaki Makaurau.

By placing these faces together, performing emotion against one another, Ireland emphasises the social reality of identity. Identity exchange is a comic staple, from Shakespeare through Chaplin, up to Jamie Lee Curtis and Lindsay Lohan in the body-swap comedy Freaky Friday (2003). The outcome is farce. The first paintings we encounter are arranged in the Freudian trinity: id, ego, and superego. Who is your favourite comedy trio? Harpo, Chico, & Groucho? The Three Stooges? Alvin and the Chipmunks?

Hannah Ireland’s gooey palette and broad grins suggest the Klasky Csupo grotesquerie of Nickelodeon’s Aaahh!!! Real Monsters. In this early-90s cartoon three young monsters attend school at a town dump. From a review in Parenting magazine: “Graphic and scatological; it's just plain gross.” The dramatic analog colour of Hate to rain on your parade is enhanced by Ireland’s skillful manipulation of watercolour on canvas. It is a stain-like medium, predisposed to bruising, it’s “just plain gross”.

Hannah Ireland, Hate to rain on your parade, 2021. October–November 13th 2021, Sanc Gallery, Tāmaki Makaurau.

Images courtesy of Sanc Gallery.

![]()

Article image: sancgallery.com/, viewing Hannah Ireland’s Hate to rain on your parade online.

1. From mid-August 2021 until early November COVID-19 regulations required the closure of all Tāmaki Makaurau art galleries to public visitors.

2. Martin Gayford, A Bigger Message: Conversations with David Hockney. Thames & Hudson, London, 2016.

3. Harold Rosenberg, Saul Steinberg. Alfred A. Knopf Inc, New York, 1978, p.10.

4. Scott McCloud, Understanding Comics. Tundra Publishing, Toronto, 1993, p.36.

Hannah Ireland’s gooey palette and broad grins suggest the Klasky Csupo grotesquerie of Nickelodeon’s Aaahh!!! Real Monsters. In this early-90s cartoon three young monsters attend school at a town dump. From a review in Parenting magazine: “Graphic and scatological; it's just plain gross.” The dramatic analog colour of Hate to rain on your parade is enhanced by Ireland’s skillful manipulation of watercolour on canvas. It is a stain-like medium, predisposed to bruising, it’s “just plain gross”.

Hannah Ireland, Hate to rain on your parade, 2021. October–November 13th 2021, Sanc Gallery, Tāmaki Makaurau.

Images courtesy of Sanc Gallery.

Article image: sancgallery.com/, viewing Hannah Ireland’s Hate to rain on your parade online.

1. From mid-August 2021 until early November COVID-19 regulations required the closure of all Tāmaki Makaurau art galleries to public visitors.

2. Martin Gayford, A Bigger Message: Conversations with David Hockney. Thames & Hudson, London, 2016.

3. Harold Rosenberg, Saul Steinberg. Alfred A. Knopf Inc, New York, 1978, p.10.

4. Scott McCloud, Understanding Comics. Tundra Publishing, Toronto, 1993, p.36.

ISSN 2744-7952

Thank you for reading ︎

Vernacular logo designed by Yujin Shin

vernacular.criticism ︎