E moko, come home

by Tessa Russell

E moko, come home | Tessa Russell | Wormhole, Edgecumbe

19.06.23 | written by Hana Pera Aoake

Kia hora te marino,

Kia whakapapa pounamu te moana,

kia tere te Kārohirohi i mua i tōu huarahi.

Kia whakapapa pounamu te moana,

kia tere te Kārohirohi i mua i tōu huarahi.

Tessa Russell’s (Ngāti Rakaipaaka) E moko, come home (2023) is a single channel video work where the screen is split into a cross section of nine squares. In water, floating, and sometimes bubbling up and down, clustered together and separated apart are a number of hei tiki.1 The sound of running water permeates through the Lockwood style building, reminding us that the ground beneath us was once part of an extensive series of wetlands across the Rangitāiki plains. Hand cut hue (calabash, gourd) lamp shades made by Wormhole’s Jordan Davey-Emms provide an ambient light that reminds me of the little lights that guide your steps in a cinema. However, the dried and hollowed out shells of these plants have an obvious relationship to water also, as they were grown along the Rangitāiki awa and were used by Māori and cultures all over the world, particularly in Africa and Central and South America as bowls, ladles, taonga pūoro and as vessels for storing and carrying fresh water. Throughout the duration of the exhibition at Wormhole gallery in Edgecumbe the projected video shifts in its location around the room, while the cosy mid-century single seated couches provide a pou that very much reminds me of the comforts and associations of home.

E moko, come home is rich in meaning and provides a tuhono between different ideas and associations to water and the way that whakapapa is inscribed within bodies. Water is an inherent part of not just being Māori, but of all living beings. Human bodies are made up of almost 80% water; water literally constitutes who we are. Ko wai mātou—we are water. In Te Ahukaramuu Charles Taylor’s essay ‘Politics and knowledge: Kaupapa Maori and Matauranga Maori’, he describes the multitude of meanings that are carried in the term ‘Māori’. Māori can simply mean ‘natural’, for instance in the word ‘waimāori’, which means fresh water.2 We are nourished, shaped by, and dependent upon the waters and currents around us. When we state our pepeha we describe ourselves as a body of water. Ko Mangopiko tōku awa, I am the Mangopiko awa. It also can relate to who we are, our name, our ancestral places and the waters that sustained our ancestors.3

In Te Ao Māori, there are two genealogical pūrākau that I am always drawn to when thinking about water. The first is the separation of Ranginui and Papatūānuku with the teardrops of Rangi and the sighs or mist of Papatūānuku expressing their deep grief at being separated from one another. The heavy splashes on our head signifying Rangi’s longing for his wife, but another story suggests that Rangi had an earlier wife, Wainuiātea. Wainuiātea was the great expanse of all water and was the birthing waters from which Papatūānuku was submerged before rising out of the ocean. Wainuiātea is an amniotic fluid, the fluid in which we exist before we are born, in a space called Te Whare Wānanga, the house of learning. It is the space where we learn and grow. Wainuiātea lives in our bodies always, after all we are made of up to 80% water.

E moko, come home is rich in meaning and provides a tuhono between different ideas and associations to water and the way that whakapapa is inscribed within bodies. Water is an inherent part of not just being Māori, but of all living beings. Human bodies are made up of almost 80% water; water literally constitutes who we are. Ko wai mātou—we are water. In Te Ahukaramuu Charles Taylor’s essay ‘Politics and knowledge: Kaupapa Maori and Matauranga Maori’, he describes the multitude of meanings that are carried in the term ‘Māori’. Māori can simply mean ‘natural’, for instance in the word ‘waimāori’, which means fresh water.2 We are nourished, shaped by, and dependent upon the waters and currents around us. When we state our pepeha we describe ourselves as a body of water. Ko Mangopiko tōku awa, I am the Mangopiko awa. It also can relate to who we are, our name, our ancestral places and the waters that sustained our ancestors.3

In Te Ao Māori, there are two genealogical pūrākau that I am always drawn to when thinking about water. The first is the separation of Ranginui and Papatūānuku with the teardrops of Rangi and the sighs or mist of Papatūānuku expressing their deep grief at being separated from one another. The heavy splashes on our head signifying Rangi’s longing for his wife, but another story suggests that Rangi had an earlier wife, Wainuiātea. Wainuiātea was the great expanse of all water and was the birthing waters from which Papatūānuku was submerged before rising out of the ocean. Wainuiātea is an amniotic fluid, the fluid in which we exist before we are born, in a space called Te Whare Wānanga, the house of learning. It is the space where we learn and grow. Wainuiātea lives in our bodies always, after all we are made of up to 80% water.

Water is sacred. Not only existing in our bodies, but the wetlands, springs, rivers, streams and oceans we belong to have long been sources of food and sustenance, routes for voyaging and trade, and repositories of spiritual knowledge and a sense of identity.4 Water can cause death, as well as provide us with life. The sound of running water in E moko, come home recalls the flooding of Edgecumbe in 2017 following Cyclone Debbie, where the Rangitāiki River breached and rapidly flooded the town where this work is playing. This allusion feels pertinent given the recent devastating flooding this last summer, particularly on the East Coast of Te Ika-a-Māui in areas close to the whenua that Russell belongs to. Despite efforts to the contrary, having drained wetlands to build towns like Edgecumbe or built hydroelectric dams to power them, the power of water is not something we can control. In a time of pending ecological catastrophe it’s a reminder that these forces exist, even beyond our belief in the ability to manipulate the whenua that we live and work on.

Water contains the ability to give life and to heal. It is a part of us and it beckons us home. When I go home I will always visit my Nana on our sacred tūpuna maunga, Taupiri, where my Nana sits between two tī kouka trees and looks down on our awa, Te Waikato. When I leave this sacred place to remove the tapu layered on my skin, I run a tap of cold water and splash my head with water and wash my hands. Splashing my head protects my mana and allows my body to let go of Nana’s wairua and the wairua of others that might attach themselves to my body. As her mokopuna I carry her name ‘Hana’ and ‘Pera’ and exist as an embodiment of her and all of our tūpuna. The title ‘E moko, come home’, describes both these ideas of ‘home’ and the ontology of what it means to be a mokopuna. A way of understanding the etymology of the kupu ‘mokopuna’ is to think about the word ‘puna’, which is a fresh, clear spring of water and the only mirror Māori ever knew.5 ‘Moko’ refers to the lines tattooed across our bodies which represent our whakapapa.6 So as mokopuna we are their living, embodied reflection of our ancestors.

Water contains the ability to give life and to heal. It is a part of us and it beckons us home. When I go home I will always visit my Nana on our sacred tūpuna maunga, Taupiri, where my Nana sits between two tī kouka trees and looks down on our awa, Te Waikato. When I leave this sacred place to remove the tapu layered on my skin, I run a tap of cold water and splash my head with water and wash my hands. Splashing my head protects my mana and allows my body to let go of Nana’s wairua and the wairua of others that might attach themselves to my body. As her mokopuna I carry her name ‘Hana’ and ‘Pera’ and exist as an embodiment of her and all of our tūpuna. The title ‘E moko, come home’, describes both these ideas of ‘home’ and the ontology of what it means to be a mokopuna. A way of understanding the etymology of the kupu ‘mokopuna’ is to think about the word ‘puna’, which is a fresh, clear spring of water and the only mirror Māori ever knew.5 ‘Moko’ refers to the lines tattooed across our bodies which represent our whakapapa.6 So as mokopuna we are their living, embodied reflection of our ancestors.

Tessa Russell, E moko, come home (2023). Interactive area for visitors to record thoughts about home. Photo: Jordan Davey-Emms

Russell’s hei tiki provide another tuhono to the wāhine atua, Hine-te-iwaiwa, who is associated with raranga, fertility, childbirth and the cycles of the moon. Hei tiki were traditionally worn by wāhine trying to fall hapū. The immersive and fluid bobbing of these hei tiki also recalls the great voyages made from Hawaiki by our tūpuna who were guided by these cycles of the moon, the ocean’s currents, the flight paths of manu and the winds of Tāwhirimatea who guided them to their new home in Aotearoa. These hei tiki look as though they are floating in a bathtub. Immediately with the idea of ‘home’, I thought of domestic labour: washing the clothes, washing the dishes, washing the floors and caring for children. I also thought of Wainuiātea and the whakapapa process that has existed within mammals and other animals for 93 million years where the foetal cells of my daughter will reside in my body for decades still and my cells will also stay in my daughter’s blood and tissues for decades, including in organs like the pancreas, heart, and skin. She is a part of me and I am a part of her. We are connected together through these strands of DNA but also water, where my tūpuna made home in Papamoa and in and around Tauranga moana, and my daughter’s father’s tūpuna landed both at Te Atua awa (Tarawera awa) and Whakatāne. The waterways of whakapapa are entwined both through the currents that guide it across this whenua, but also as a web of veins that live inside of bodies. Recently, during my nightly routine of washing my daughter, dressing her and getting her ready for bed I think about the image of Russell’s hei tiki as embryos and that water remains the building blocks of all life.

The green in the hei tiki and the way the light shines through different tiki in different shots, reminds me of the many different kinds of pounamu. Some shimmer like the heat of air that rises from the ground on hot days, that’s said to be Tāne Rore dancing for his mother, Hine-Raumati. Others contain lines, speckles or discolorations. It also connects me to another home, the Arahura river on the West Coast of Te Waipounamu where I whakapapa to through my mother. Although Russell’s hei tiki might simply be plastic, I think of pounamu. In a kōrero I had with my whanauka, the artist Fiona Pardington, who also belongs to the Arahura river, she described the process of photographing hei tiki by communicating with them and asking them for permission to photograph them as sentient beings. In this process, Pardington acknowledged the wairua of those who wore and who had owned these taonga as being present and inscribed within these objects whose pounamu eyes stare back at us. The kupu ‘wairua’ can be described as ‘wai’, as in water, and ‘rua’, as in two, so two worlds that are interconnected. According to Rangimārie Te Turuki Arikirangi Rose Pere, “Wairua loosely translated means two waters… water in all its forms comes from two sources...it either arrives as rain from Ranginui or it comes as a spring as waiū from Papatūānuku”.7 Wairua is said to be implanted in the embryo by our parents and lies dormant until our eyes form.8 To ignore wairua is to become spiritually blind or kahupō. Wairua is immortal, even beyond death, and can go wandering and live in seemingly banal objects like hei tiki. The wairua inherent within hei tiki describes our relation to water, because all life is born of water, so without water we don’t exist; Mēnā ki te kore ki te wai.

According to pūrākau of Ngāi Tahu, the story of pounamu follows a Taniwha named Poutini who stole the beautiful Waitaiki from her home in the Bay of Plenty, where she lived with her husband Tamaahua. Tamaahua chased Poutini and Waitaiki down Te Ika-a-Māui to Te Wai Pounamu, where he tracked them by following the fires Poutini made in order to keep Waitaiki warm. In the remains of each fire, Poutini left precious stones. Eventually Poutini made it to Piopiotahi and realised there was no escape. He transformed Waitaiki into Pounamu and laid her down in the riverbeds of the Arahura river. When Tamaahua discovered his beloved had been turned into pounamu his tangi filled the air with grief and was imbued into the stone. The grief of Tamaahua glistens in Russell’s hei tiki. These taonga allude to the shimmering light of the sun on the waves of water and in the ngahere when fractals of light seep in through the tops of trees. It reminds us that our kinships were plural, we existed and still exist as multitudes where we performed various ceremonial practices and visual expressions.9 Despite the coming of evangelical missionaries and land-hungry settlers, we as Māori existed and resisted and searched instead for the shimmering light found in taonga like hei tiki, which were and are repositories of mana, and of the wairua of those long passed.

The green in the hei tiki and the way the light shines through different tiki in different shots, reminds me of the many different kinds of pounamu. Some shimmer like the heat of air that rises from the ground on hot days, that’s said to be Tāne Rore dancing for his mother, Hine-Raumati. Others contain lines, speckles or discolorations. It also connects me to another home, the Arahura river on the West Coast of Te Waipounamu where I whakapapa to through my mother. Although Russell’s hei tiki might simply be plastic, I think of pounamu. In a kōrero I had with my whanauka, the artist Fiona Pardington, who also belongs to the Arahura river, she described the process of photographing hei tiki by communicating with them and asking them for permission to photograph them as sentient beings. In this process, Pardington acknowledged the wairua of those who wore and who had owned these taonga as being present and inscribed within these objects whose pounamu eyes stare back at us. The kupu ‘wairua’ can be described as ‘wai’, as in water, and ‘rua’, as in two, so two worlds that are interconnected. According to Rangimārie Te Turuki Arikirangi Rose Pere, “Wairua loosely translated means two waters… water in all its forms comes from two sources...it either arrives as rain from Ranginui or it comes as a spring as waiū from Papatūānuku”.7 Wairua is said to be implanted in the embryo by our parents and lies dormant until our eyes form.8 To ignore wairua is to become spiritually blind or kahupō. Wairua is immortal, even beyond death, and can go wandering and live in seemingly banal objects like hei tiki. The wairua inherent within hei tiki describes our relation to water, because all life is born of water, so without water we don’t exist; Mēnā ki te kore ki te wai.

According to pūrākau of Ngāi Tahu, the story of pounamu follows a Taniwha named Poutini who stole the beautiful Waitaiki from her home in the Bay of Plenty, where she lived with her husband Tamaahua. Tamaahua chased Poutini and Waitaiki down Te Ika-a-Māui to Te Wai Pounamu, where he tracked them by following the fires Poutini made in order to keep Waitaiki warm. In the remains of each fire, Poutini left precious stones. Eventually Poutini made it to Piopiotahi and realised there was no escape. He transformed Waitaiki into Pounamu and laid her down in the riverbeds of the Arahura river. When Tamaahua discovered his beloved had been turned into pounamu his tangi filled the air with grief and was imbued into the stone. The grief of Tamaahua glistens in Russell’s hei tiki. These taonga allude to the shimmering light of the sun on the waves of water and in the ngahere when fractals of light seep in through the tops of trees. It reminds us that our kinships were plural, we existed and still exist as multitudes where we performed various ceremonial practices and visual expressions.9 Despite the coming of evangelical missionaries and land-hungry settlers, we as Māori existed and resisted and searched instead for the shimmering light found in taonga like hei tiki, which were and are repositories of mana, and of the wairua of those long passed.

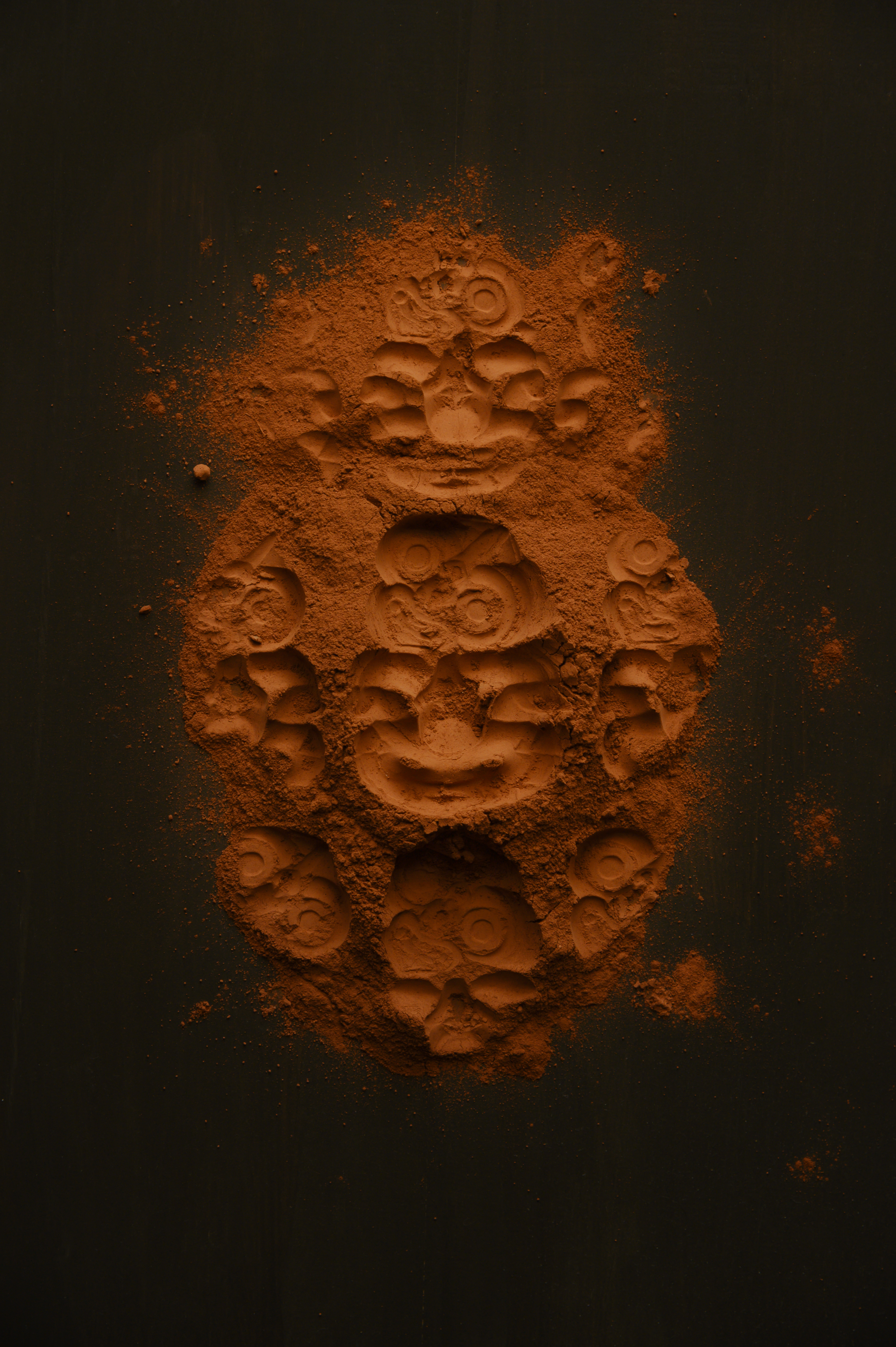

Tessa Russell, #itsnotaboutatie, 2021. Imprinted kōkōwai mound. Courtesy of the artist

In another work titled #itsnotaboutatie (2021), which toured the country as a finalist in the Kiingi Tuheitia Portraiture prize in 2021, Russell presented a loose mound of kōkōwai from her Ngāti Rakaipaaka rohe with a hei tiki indented into the kōkōwai. This use of kōkōwai, or red ochre, speaks to an ancient practice that stretches across not just Te Moana-nui-a-kiwa, but across many Indigenous cultures. Red represents the origin story of the separation of Papatūānuku and Ranginui, where the blood of Ranginui was spilt and soaked into Papatūānuku, creating kōkōwai.10 The colour red is associated with rituals of tapu that were associated with atua. In various rituals it was used as a form of protection by or from certain gods, and was painted onto objects, a person, post or even a place to indicate being in a state of tapu.11 Kōkōwai was often used to coat places where a tūpāpaku had been and was also smeared on the body preparing the deceased for the next life. During second burials the koiwi would be washed and painted in kōkōwai. The title ‘#itsnotaboutatie’ refers to an incident in New Zealand Parliament where Te Pati Māori MP, Rawiri Waititi was ejected by the former house speaker, Trevor Mallard, from Parliament’s debating chamber for wearing a hei tiki instead of a tie. Russell made #itsnotaboutatie in response to a social media post by Māori labour MP Tamati Coffey disparaging Waititi for not wearing a tie. Russell wanted to both critique the lateral violence of Coffey’s statements and internalised racism, but also to show how a hei tiki is a representation of one's ancestor, whereas a tie is a piece of fabric.

Encased in a Wardian vitrine reflecting both museological modes of display and the preciousness of the kōkōwai inside of it, Russell depicted her wahine tūpuna Rongomaiwahine. Rongomaiwahine is an ancestor to many people across the Māhia Peninsula, including Wairoa, Hawkes Bay and the Wairarapa. Originally married to Tamatakutai, a master carver, Rongomaiwahine was known for her beauty and intelligence. After Tamatakutai drowned she eventually remarried the infamous Kahungunu who had longed for her. Their descendants include Rakaipaaka, of whom Russell has direct whakapapa ties. #itsnotaboutatie showed one central hei tiki in the centre with others imprinted around it, indicating the layers of descent within whakapapa. Particle remnants of this work were inevitably left at each gallery while it toured the country, alongside the other finalists from the Kiingi Tuheitia portraiture prize. This again indicates the way that whakapapa leaves connections wherever it goes, especially as it travels and migrates across waterways.

Encased in a Wardian vitrine reflecting both museological modes of display and the preciousness of the kōkōwai inside of it, Russell depicted her wahine tūpuna Rongomaiwahine. Rongomaiwahine is an ancestor to many people across the Māhia Peninsula, including Wairoa, Hawkes Bay and the Wairarapa. Originally married to Tamatakutai, a master carver, Rongomaiwahine was known for her beauty and intelligence. After Tamatakutai drowned she eventually remarried the infamous Kahungunu who had longed for her. Their descendants include Rakaipaaka, of whom Russell has direct whakapapa ties. #itsnotaboutatie showed one central hei tiki in the centre with others imprinted around it, indicating the layers of descent within whakapapa. Particle remnants of this work were inevitably left at each gallery while it toured the country, alongside the other finalists from the Kiingi Tuheitia portraiture prize. This again indicates the way that whakapapa leaves connections wherever it goes, especially as it travels and migrates across waterways.

I often think of the whakataukī Kia hora te marino, Kia whakapapa pounamu te moana, kia tere te Kārohirohi i mua i tōu huarahi, as a way of clearing my mind and of imagining the glistening seas of our tūpuna arriving from Hawaiki. It is this image that I think of when I sweat and cry salty water, because I know that the ocean is in my blood.12 Russell and I through our various whakapapa ties share a connection through the Tākitimu waka, which is a link that is bound by the many ocean currents our tūpuna travelled before settling in different parts of the motu. Watching E moko, come home was relaxing. It is a hypnotic, beautiful and deceptively simple work. It draws out so many meanings that are personal, but also speak to broader ideas of how to understand places where we belong and whom we belong to. Its rhythm reminds us of different ways of considering time. For Māori, time is unified and nonlinear; past, present and future are one.13 This can be surmised in the whakataukī, I ngā wā o mua—time is at the front. E moko, come home most importantly is a reminder that we exist in a continuum whereby as mokopuna we are deeply connected and shaped by whakapapa, and whakapapa provides the home that like water exists always inside of us.

Kia hora te marino,

Kia whakapapa pounamu te moana,

kia tere te Kārohirohi i mua i tōu huarahi

1. Hei tiki are ornamental pendants made of pounamu that are worn around the neck and have been carved to depict a human-like body, with heads slightly tilted and both hands resting on their thighs. The eyes on hei tiki are generally made of paua shell inlay, and are much bigger than those found on tiki which are carved from wood.

2. Te Ahukaramū Charles Taylor, “Politics and Knowledge: Kaupapa Maori and Matauranga Maori”, New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, vol 47, no.2, 2012, 31

3. Ariana Tikao, “Once there was nothing but water”, Māori Moving Image. Bridget Reweti and Melanie Oliver (eds). (Christchurch: Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, 2022), 156

4. Tina Ngata, “Wai Māori: a Māori perspective on the freshwater debate”, The Spinoff, November 6, 2018. Accessed 2nd May, 2023

https://thespinoff.co.nz/atea/06-11-2018/wai-maori-a-maori-perspective-on-the-freshwater-debate

5. Robert Mahuta, “Foreword”, The Kīngitanga: the People of the Māori King Movement. Essays from The Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Auckland University Press & Bridget Williams Books: Auckland, New Zealand, 1997, vii

6. ibid

7. Rangimārie Te Turuki Arikirangi Rose Pere, Ako: concepts and learning in the Maori tradition. (Wellington, New Zealand: Te Kohanga Reo National Trust Board, 1994), 33

8. Hirini Moko Mead, Tikanga Māori: living by Māori values. (Wellington: Huia Publishers, 2003), 55

9. Hana Pera Aoake quoting A Moment of True Decolonization #08 Léuli Eshrāghi: Priority to Indigenous Pleasures on The Funambulist, in “Wailing Waiata—Takataapui marronage, ways of being, and essa may ranapiri’s ransack”, Minarets, https://minarets.info/ransack-essa-may-ranapiri/ (2020)

10. Louise Furey, “Use of Kōkōwai In Traditional Māori Society”, Five Māori Painters. Ngahiraka Mason (ed). (Auckland: Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, 2014), 75

11. Ibid, 75.

12. “We sweat and cry salt water, so we know that the ocean is really in our blood.” Epeli Hauʻofa quoting Teresia Teaiwa in Epeli Hauʻofa, We are the Ocean: Selected Works. (Honolulu, Hawaiʻi: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2008), 392

13. Te Ahukaramū Charles Royal, Te Haurapa: An Introduction to Researching Tribal Histories and Traditions. (Wellington: Bridget Williams Books, 1992), 20-21

Article image: Tessa Russell, E moko, come home (2023). Installation view of projection on Lockwood wall. Photo: Jordan Davey-Emms

Tessa Russell, E moko, come home, 2023. 3 May – 3 June at Wormhole, Edgecumbe.

Kia hora te marino,

May peace be widespread,

Kia whakapapa pounamu te moana,

may the sea glisten like greenstone,

kia tere te Kārohirohi i mua i tōu huarahi

and may the shimmer of light guide you on your way.

1. Hei tiki are ornamental pendants made of pounamu that are worn around the neck and have been carved to depict a human-like body, with heads slightly tilted and both hands resting on their thighs. The eyes on hei tiki are generally made of paua shell inlay, and are much bigger than those found on tiki which are carved from wood.

2. Te Ahukaramū Charles Taylor, “Politics and Knowledge: Kaupapa Maori and Matauranga Maori”, New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, vol 47, no.2, 2012, 31

3. Ariana Tikao, “Once there was nothing but water”, Māori Moving Image. Bridget Reweti and Melanie Oliver (eds). (Christchurch: Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, 2022), 156

4. Tina Ngata, “Wai Māori: a Māori perspective on the freshwater debate”, The Spinoff, November 6, 2018. Accessed 2nd May, 2023

https://thespinoff.co.nz/atea/06-11-2018/wai-maori-a-maori-perspective-on-the-freshwater-debate

5. Robert Mahuta, “Foreword”, The Kīngitanga: the People of the Māori King Movement. Essays from The Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Auckland University Press & Bridget Williams Books: Auckland, New Zealand, 1997, vii

6. ibid

7. Rangimārie Te Turuki Arikirangi Rose Pere, Ako: concepts and learning in the Maori tradition. (Wellington, New Zealand: Te Kohanga Reo National Trust Board, 1994), 33

8. Hirini Moko Mead, Tikanga Māori: living by Māori values. (Wellington: Huia Publishers, 2003), 55

9. Hana Pera Aoake quoting A Moment of True Decolonization #08 Léuli Eshrāghi: Priority to Indigenous Pleasures on The Funambulist, in “Wailing Waiata—Takataapui marronage, ways of being, and essa may ranapiri’s ransack”, Minarets, https://minarets.info/ransack-essa-may-ranapiri/ (2020)

10. Louise Furey, “Use of Kōkōwai In Traditional Māori Society”, Five Māori Painters. Ngahiraka Mason (ed). (Auckland: Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, 2014), 75

11. Ibid, 75.

12. “We sweat and cry salt water, so we know that the ocean is really in our blood.” Epeli Hauʻofa quoting Teresia Teaiwa in Epeli Hauʻofa, We are the Ocean: Selected Works. (Honolulu, Hawaiʻi: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2008), 392

13. Te Ahukaramū Charles Royal, Te Haurapa: An Introduction to Researching Tribal Histories and Traditions. (Wellington: Bridget Williams Books, 1992), 20-21

Article image: Tessa Russell, E moko, come home (2023). Installation view of projection on Lockwood wall. Photo: Jordan Davey-Emms

Tessa Russell, E moko, come home, 2023. 3 May – 3 June at Wormhole, Edgecumbe.

ISSN 2744-7952

Thank you for reading ︎

Vernacular logo designed by Yujin Shin

vernacular.criticism ︎